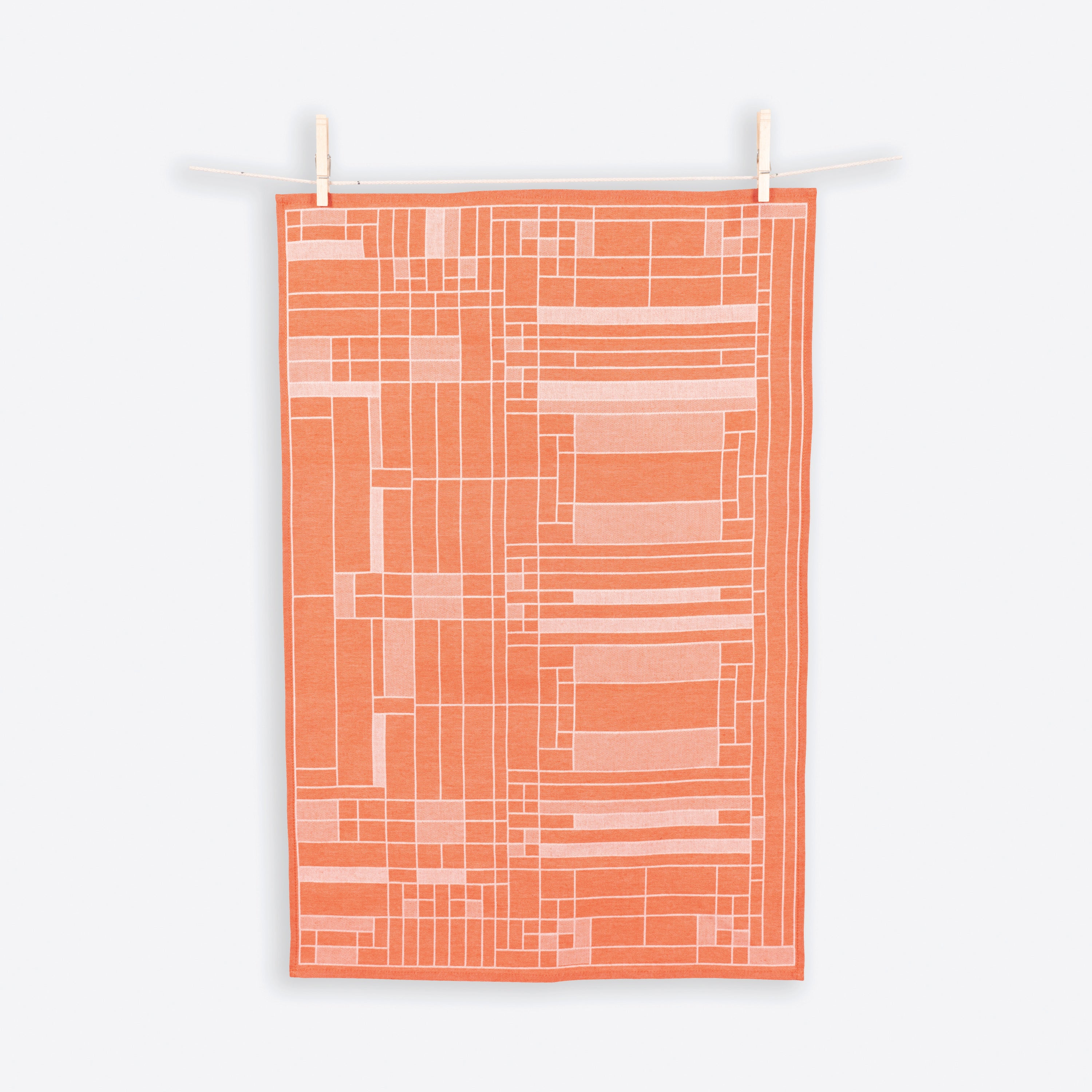

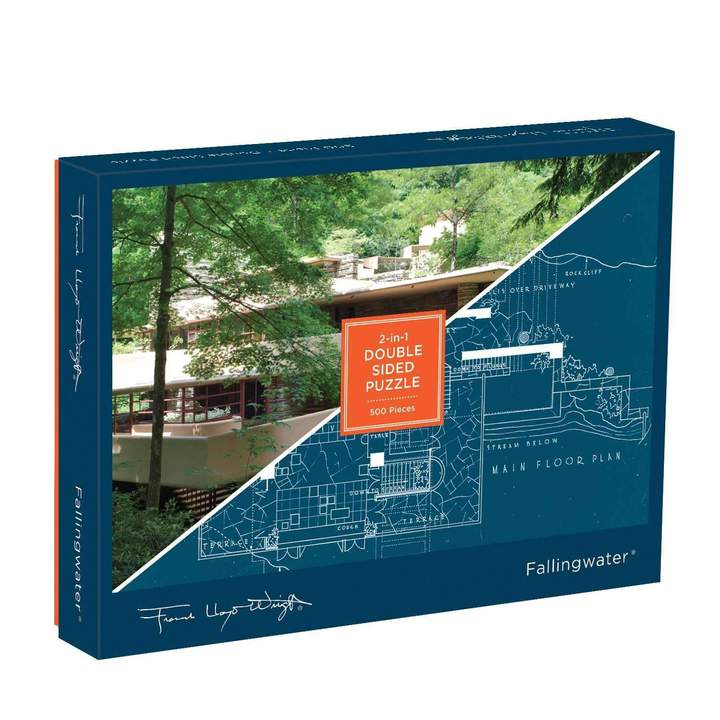

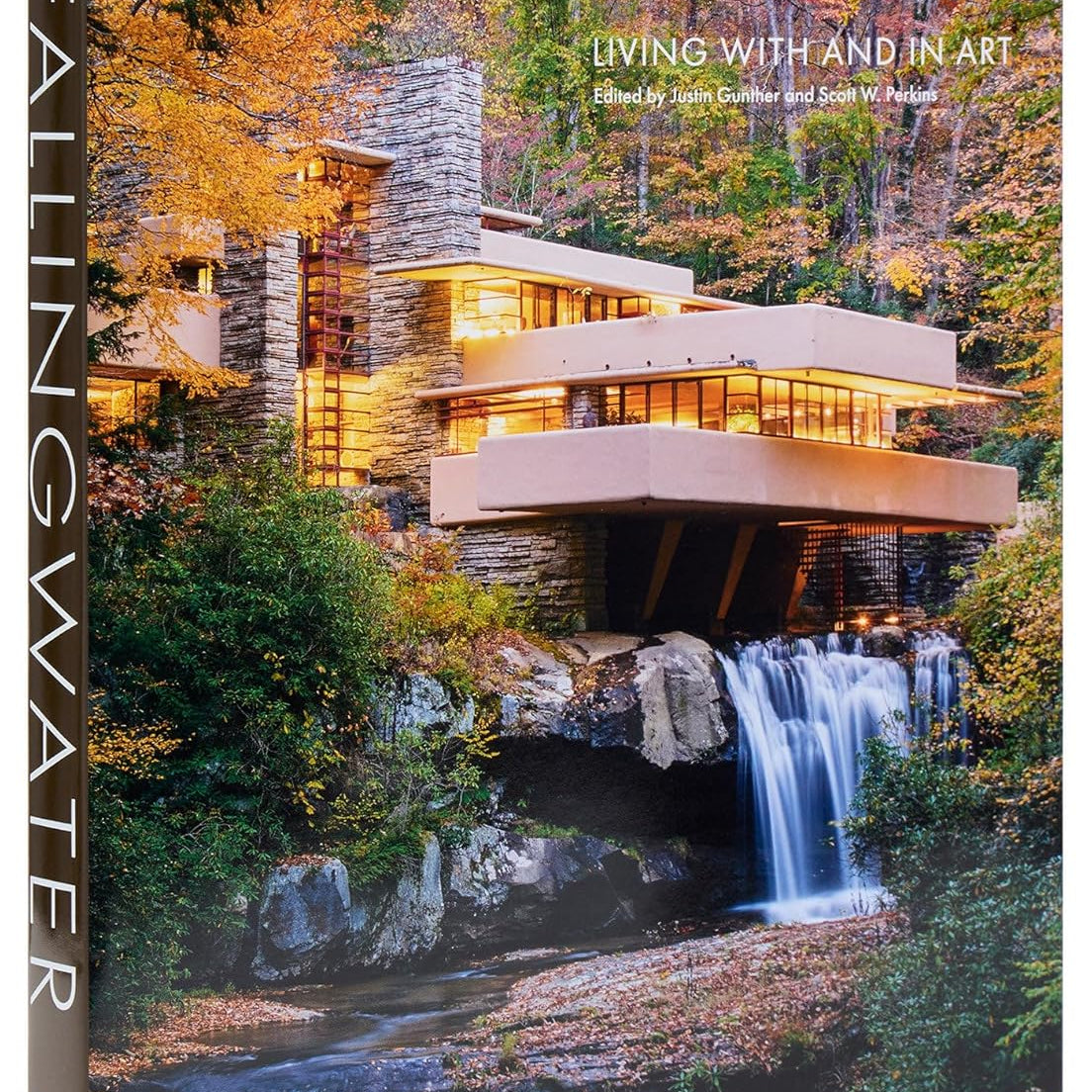

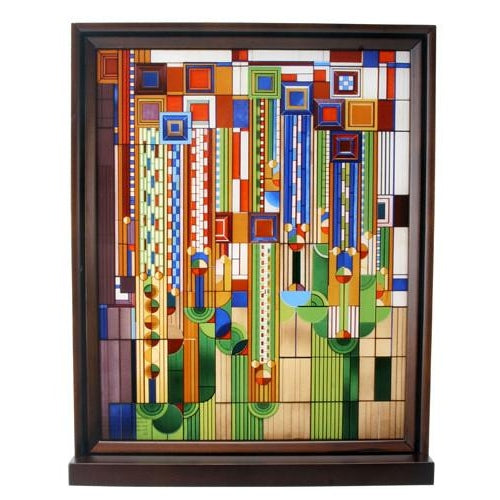

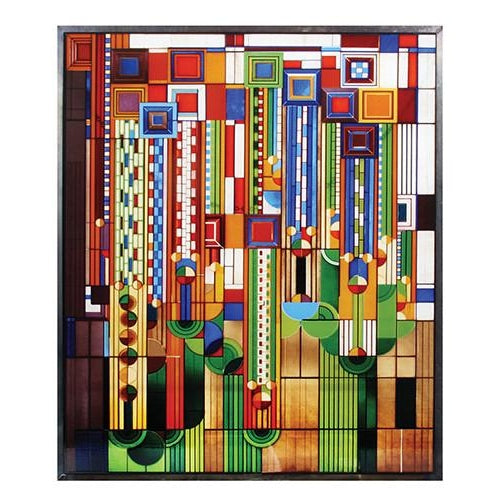

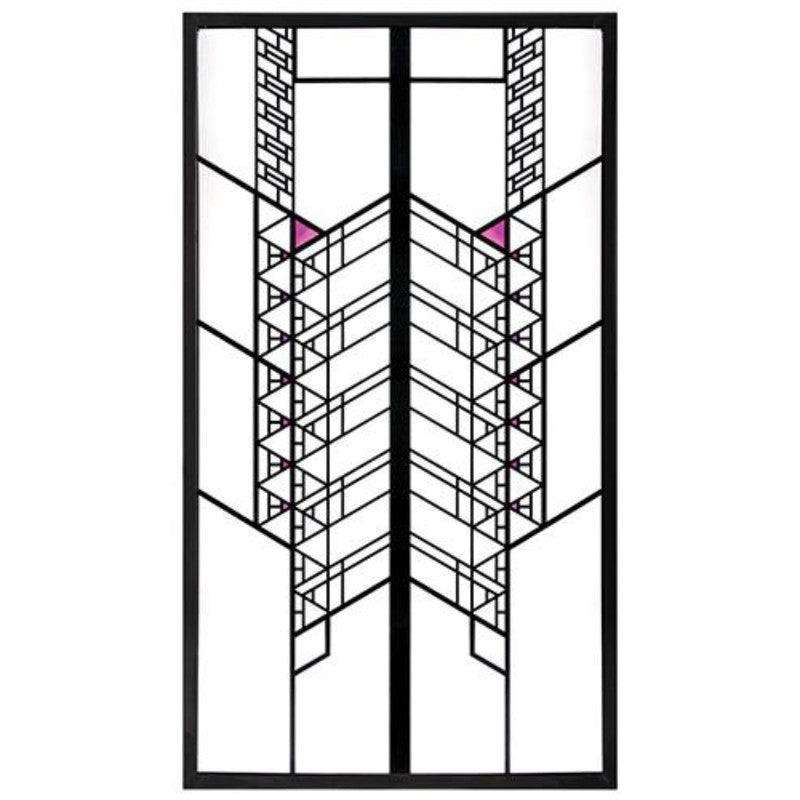

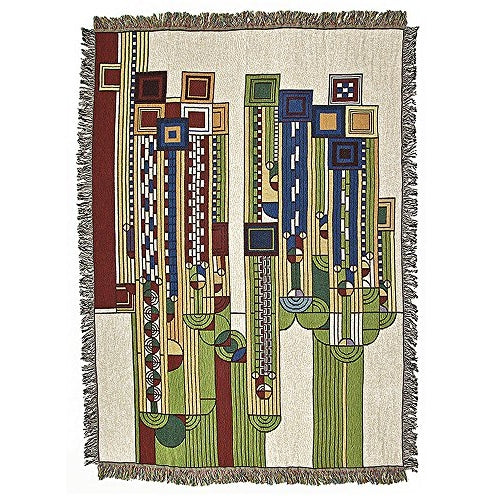

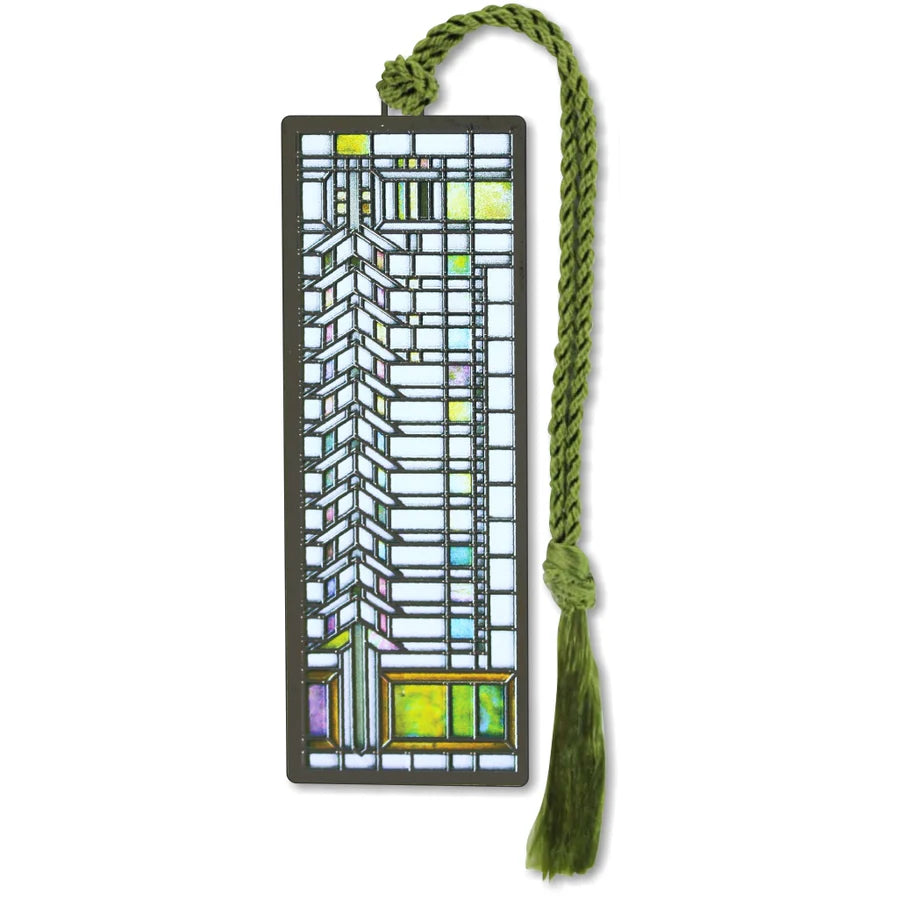

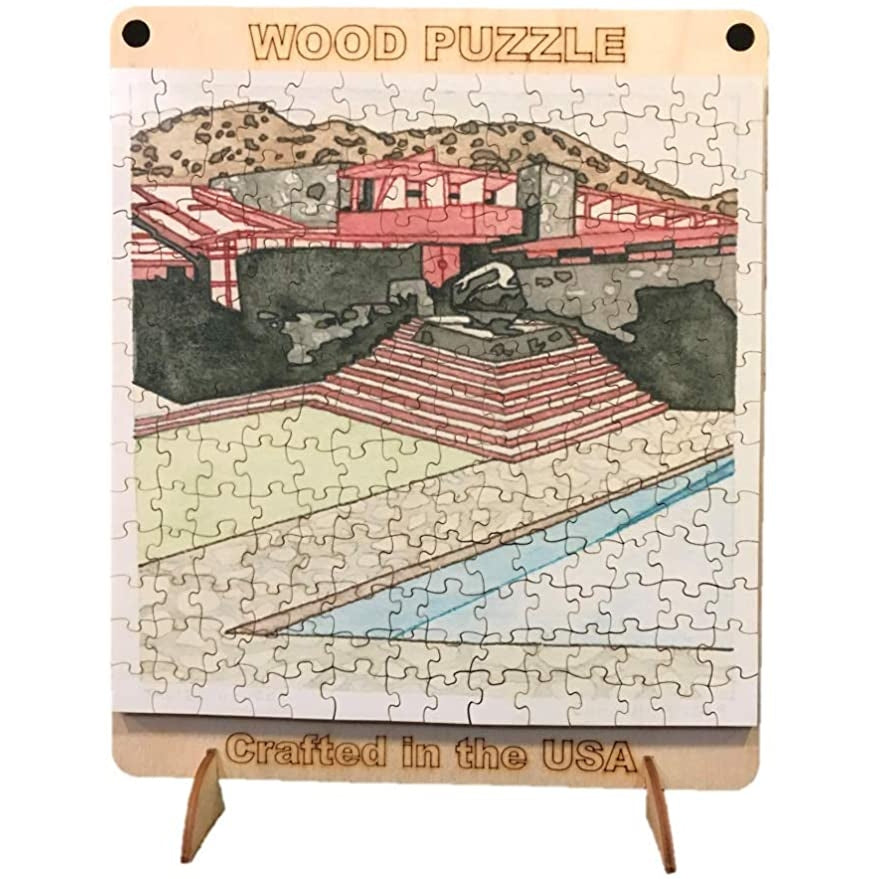

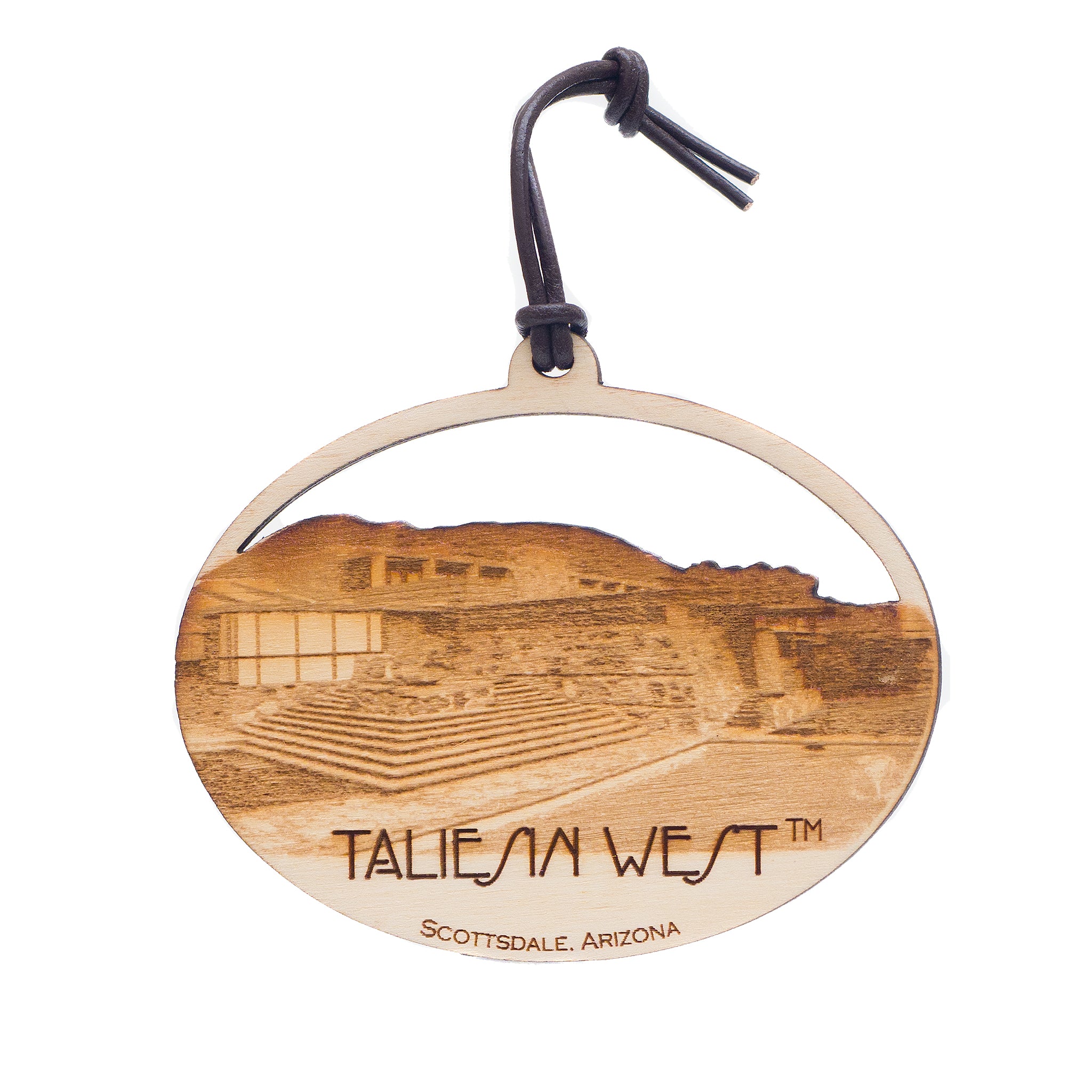

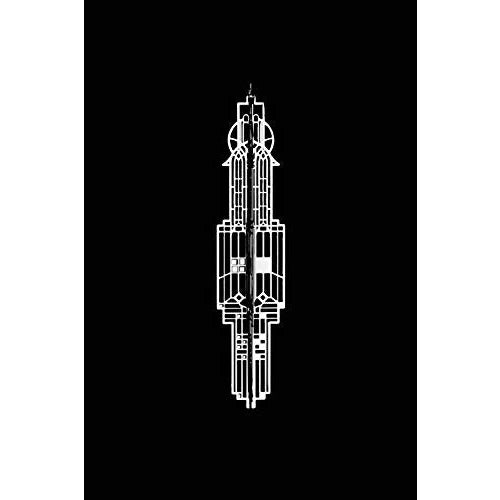

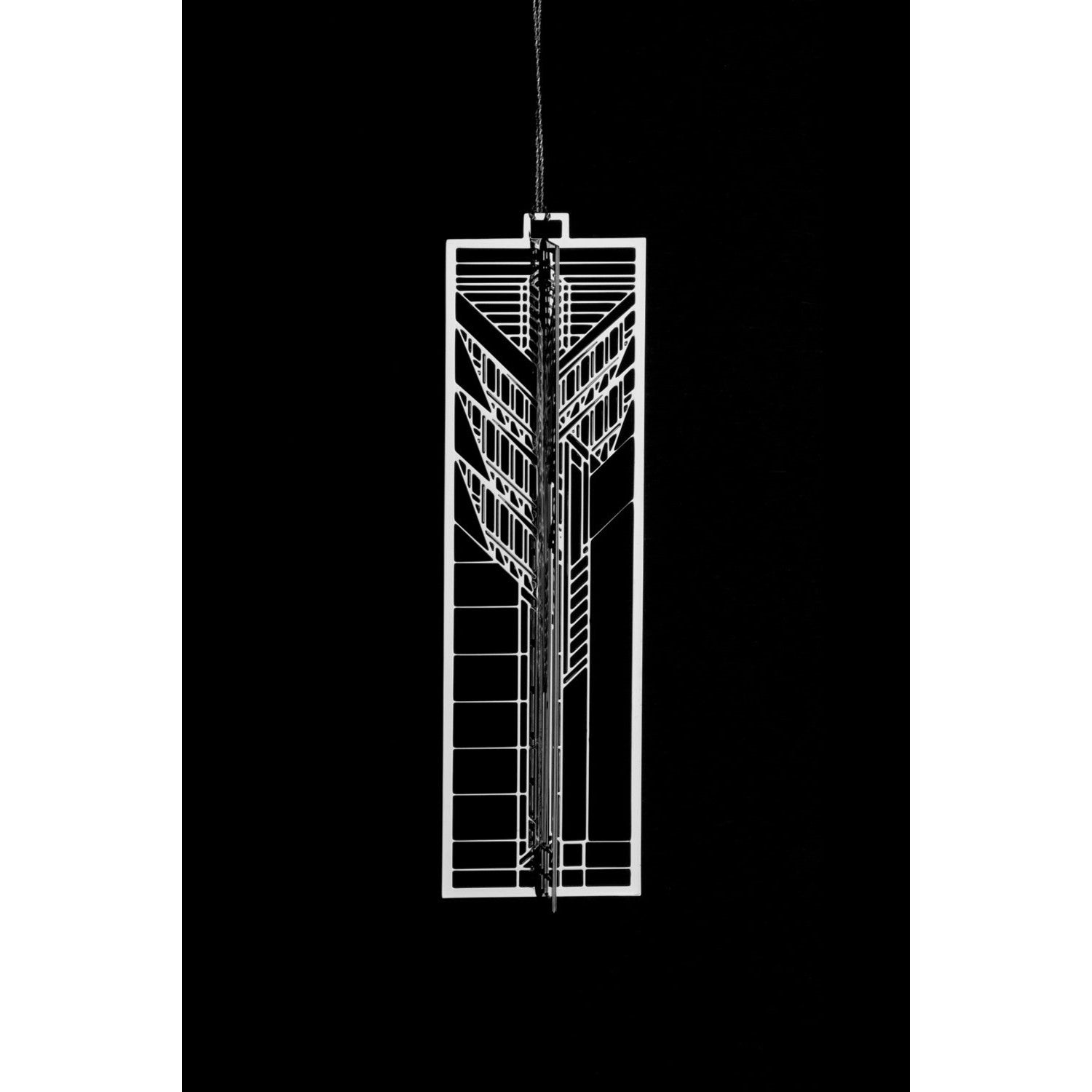

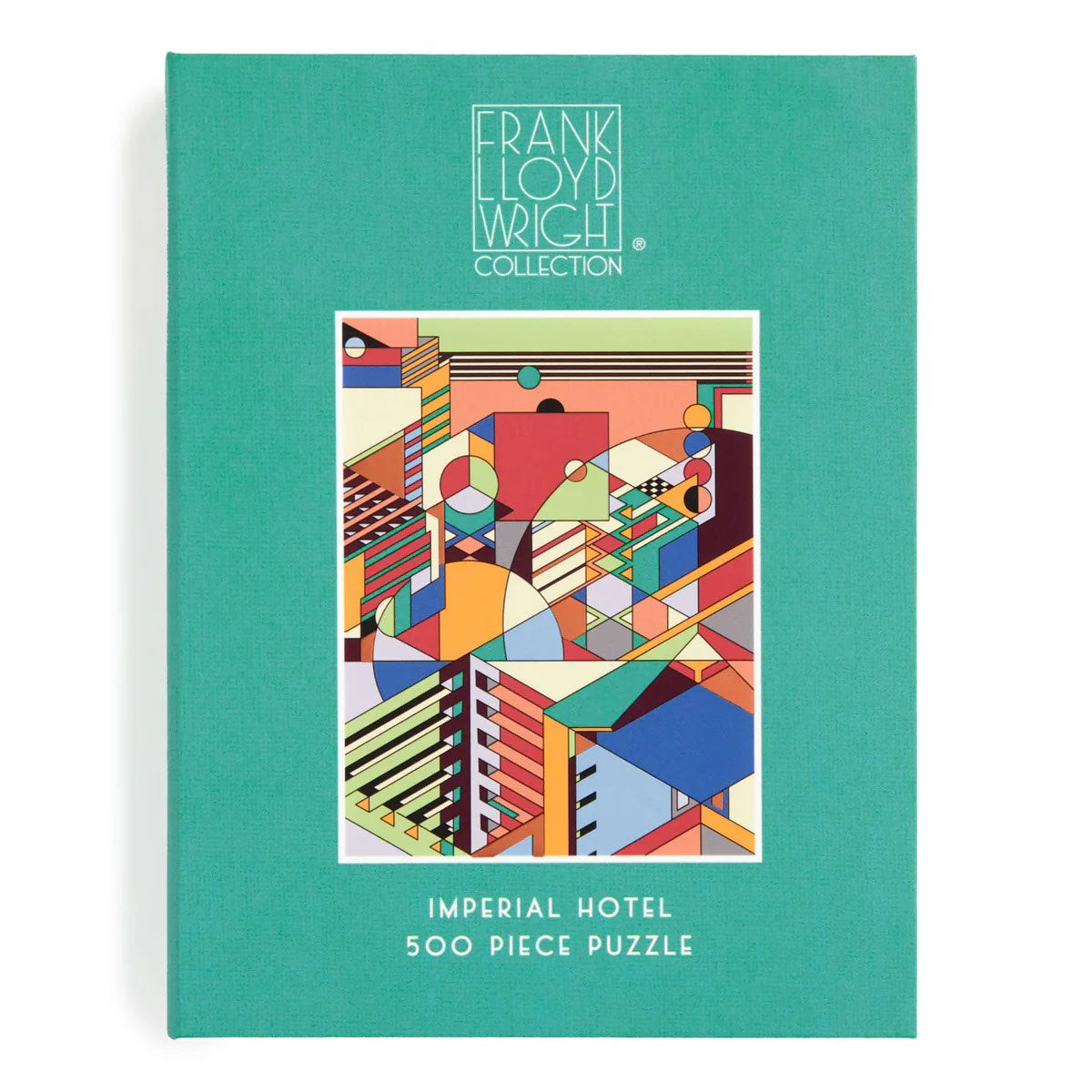

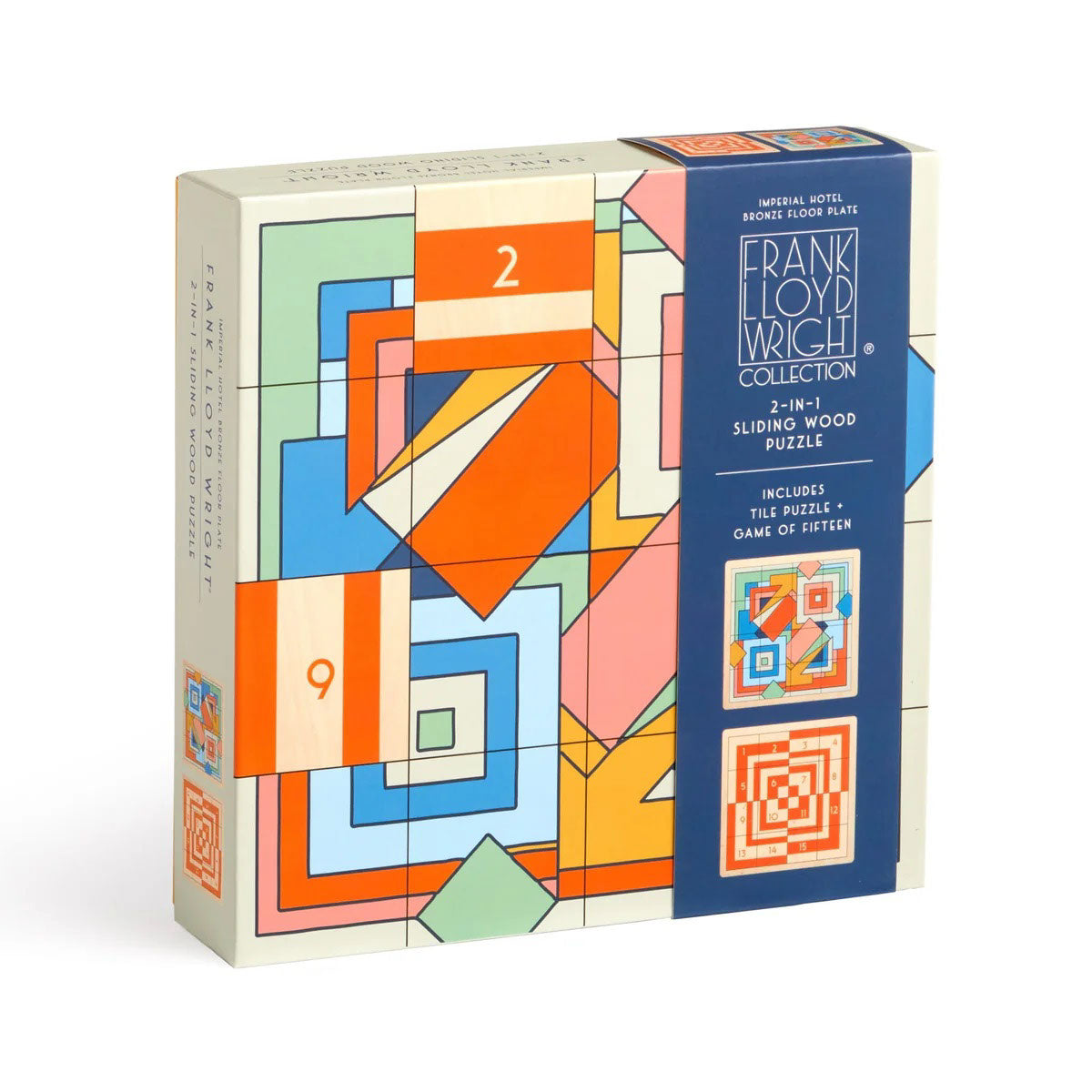

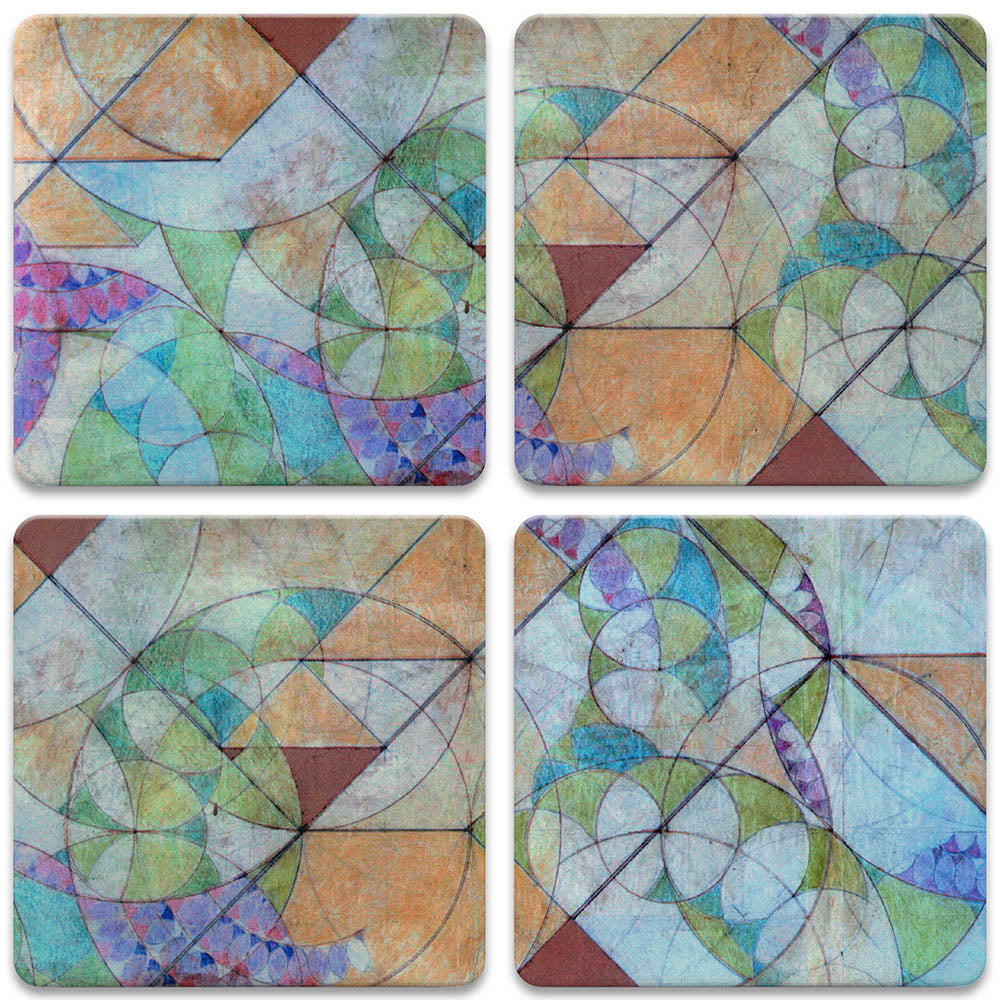

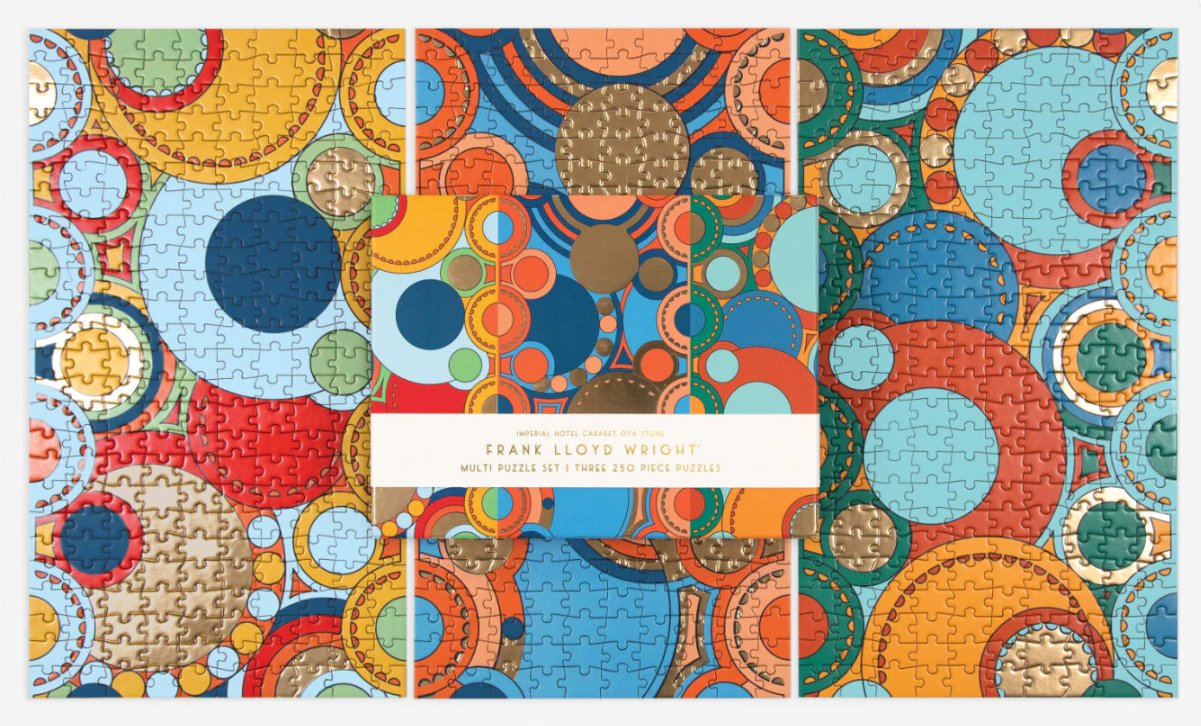

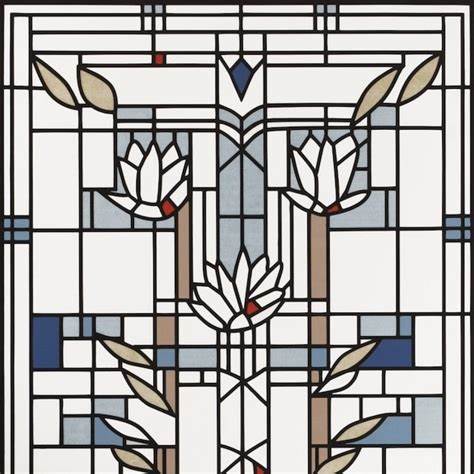

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel, built between 1917 and 1923 in Tokyo, reflected his deep appreciation for Japanese art and culture. Wright described it as neither purely American nor Japanese, but as a tribute to Japan that maintained its own individuality. The H-shaped, 250-room hotel was designed around a large courtyard and reflecting pool, with wings containing guest rooms extending toward the rear. Engineered with a floating foundation and reinforced steel, it was built to withstand Japan's frequent earthquakes.

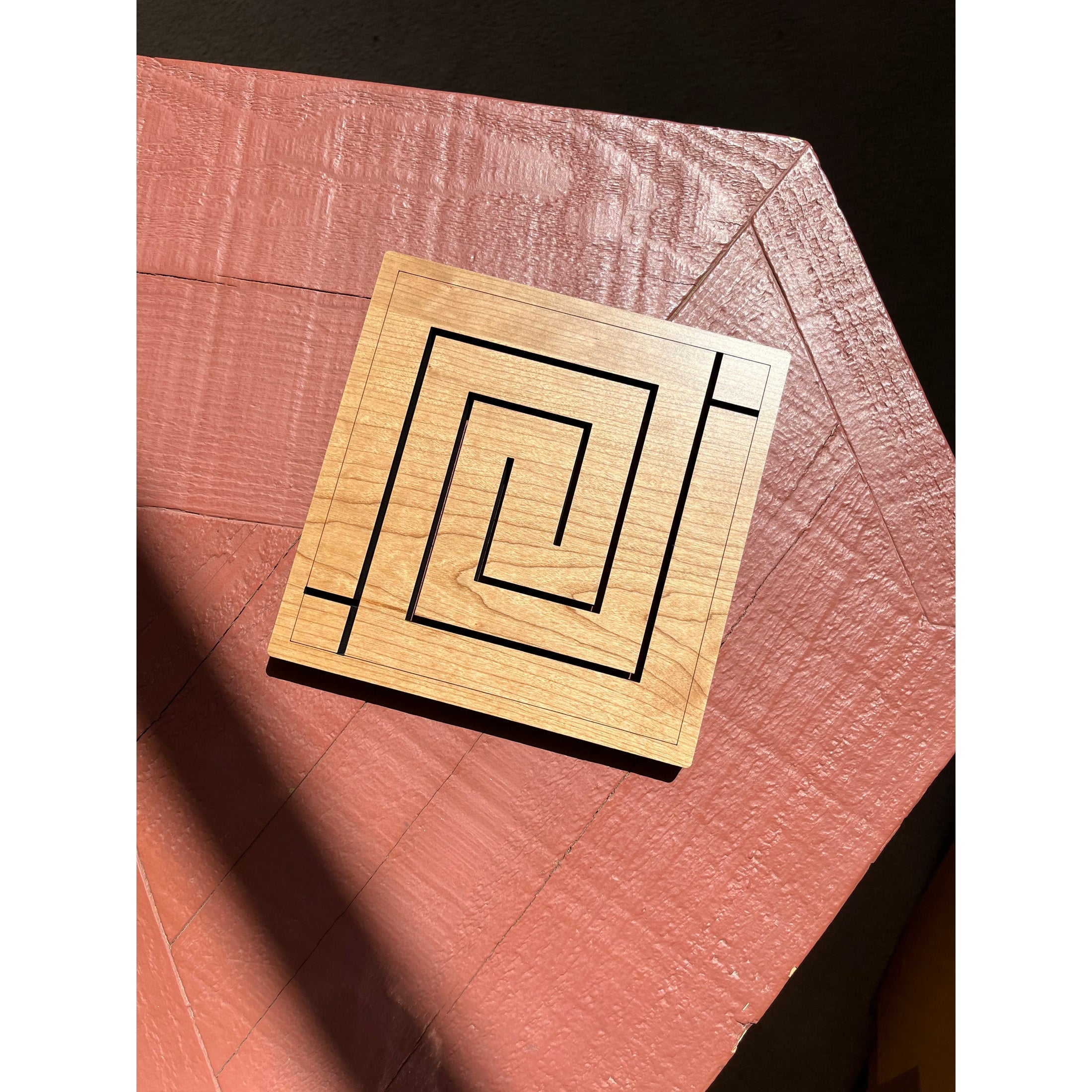

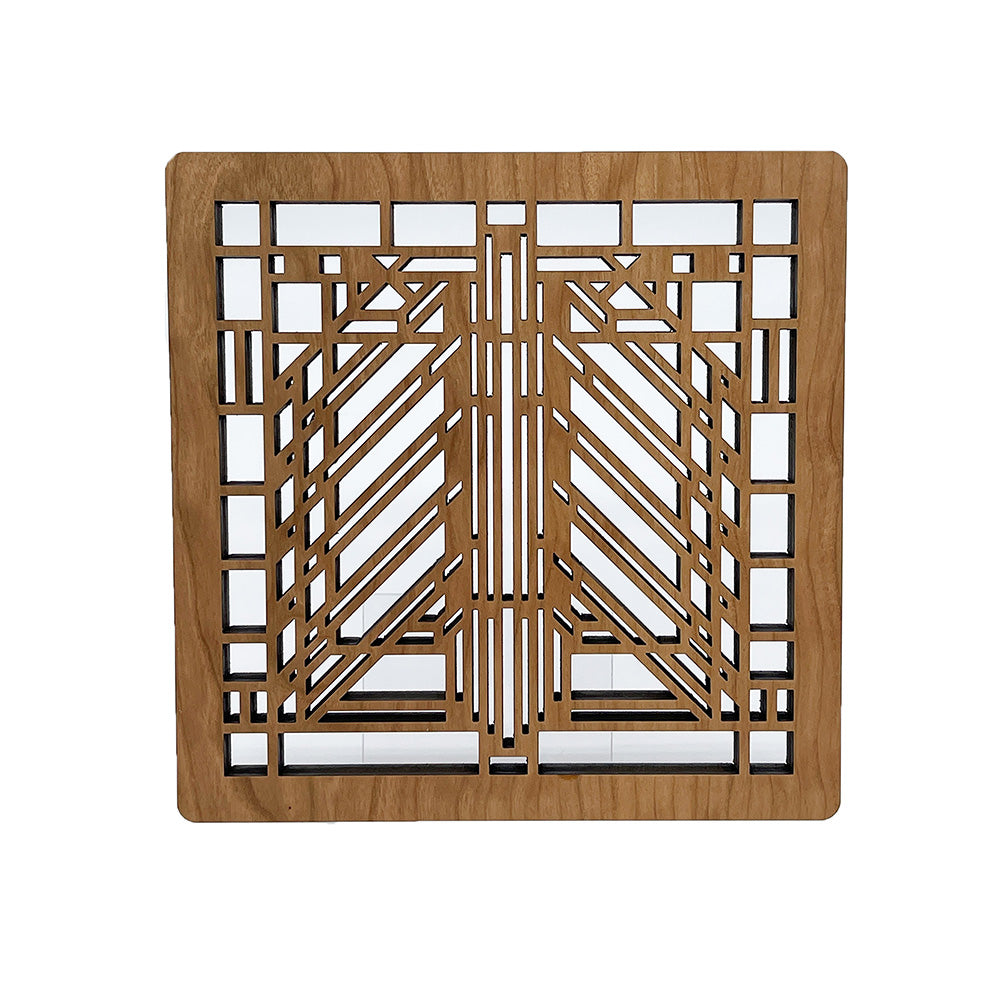

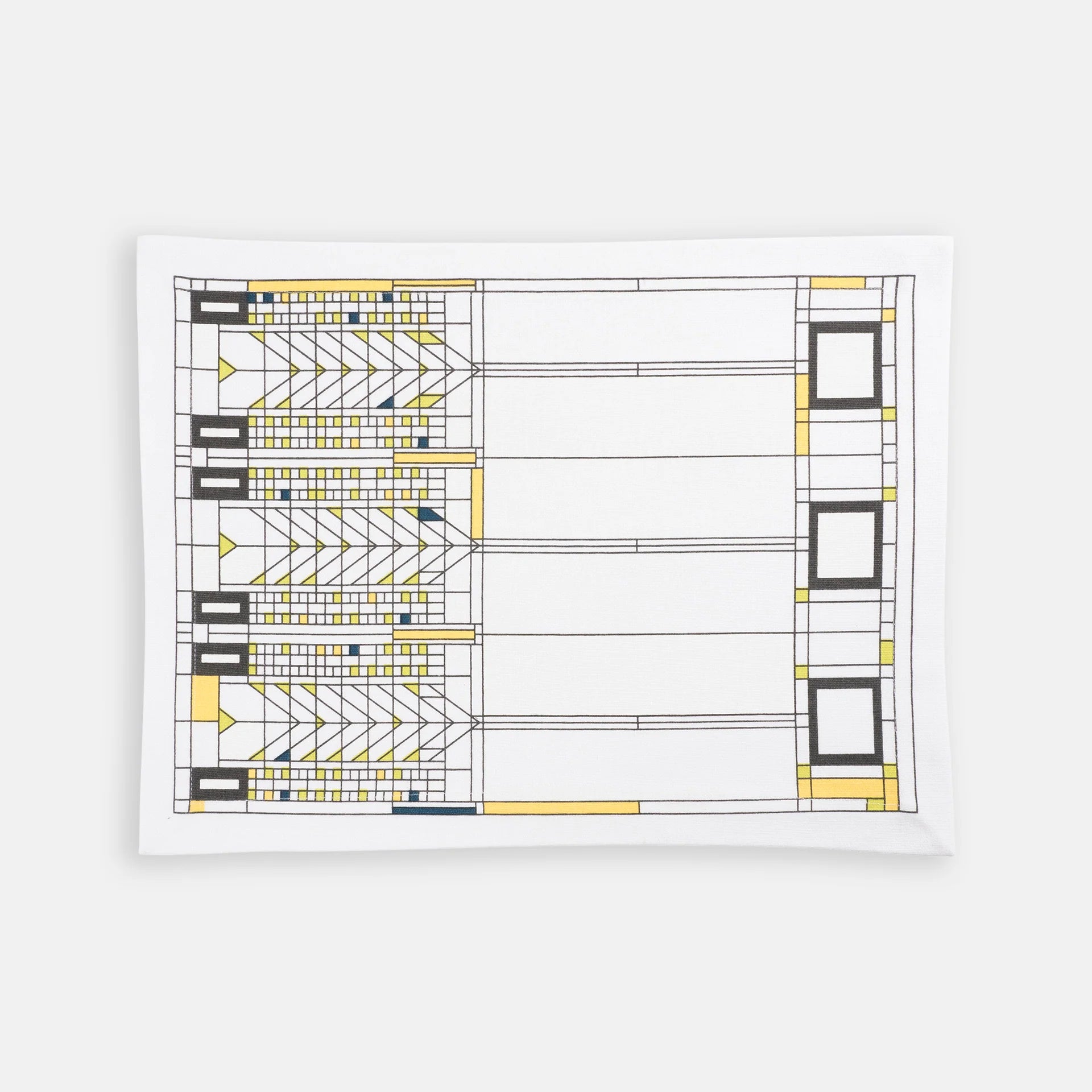

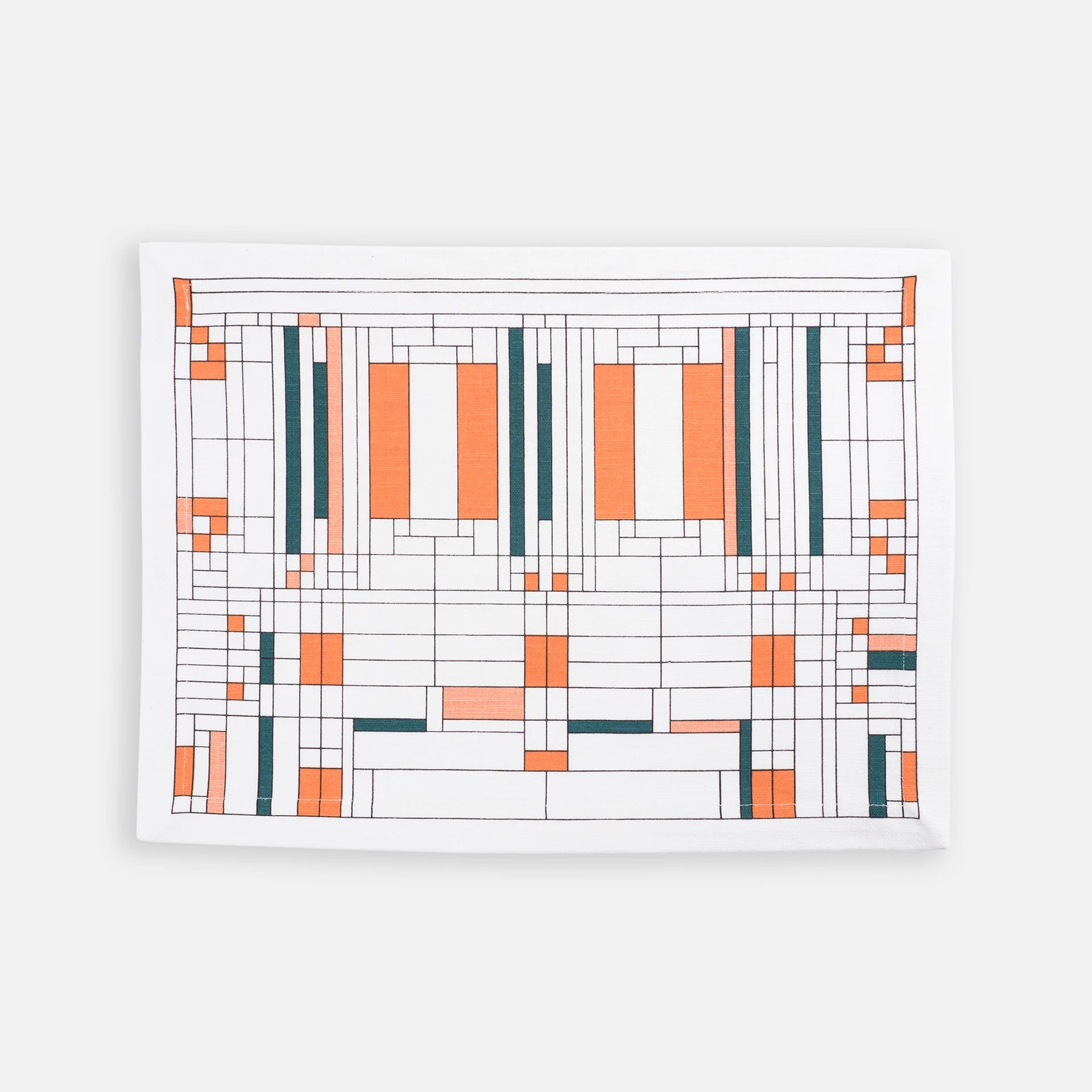

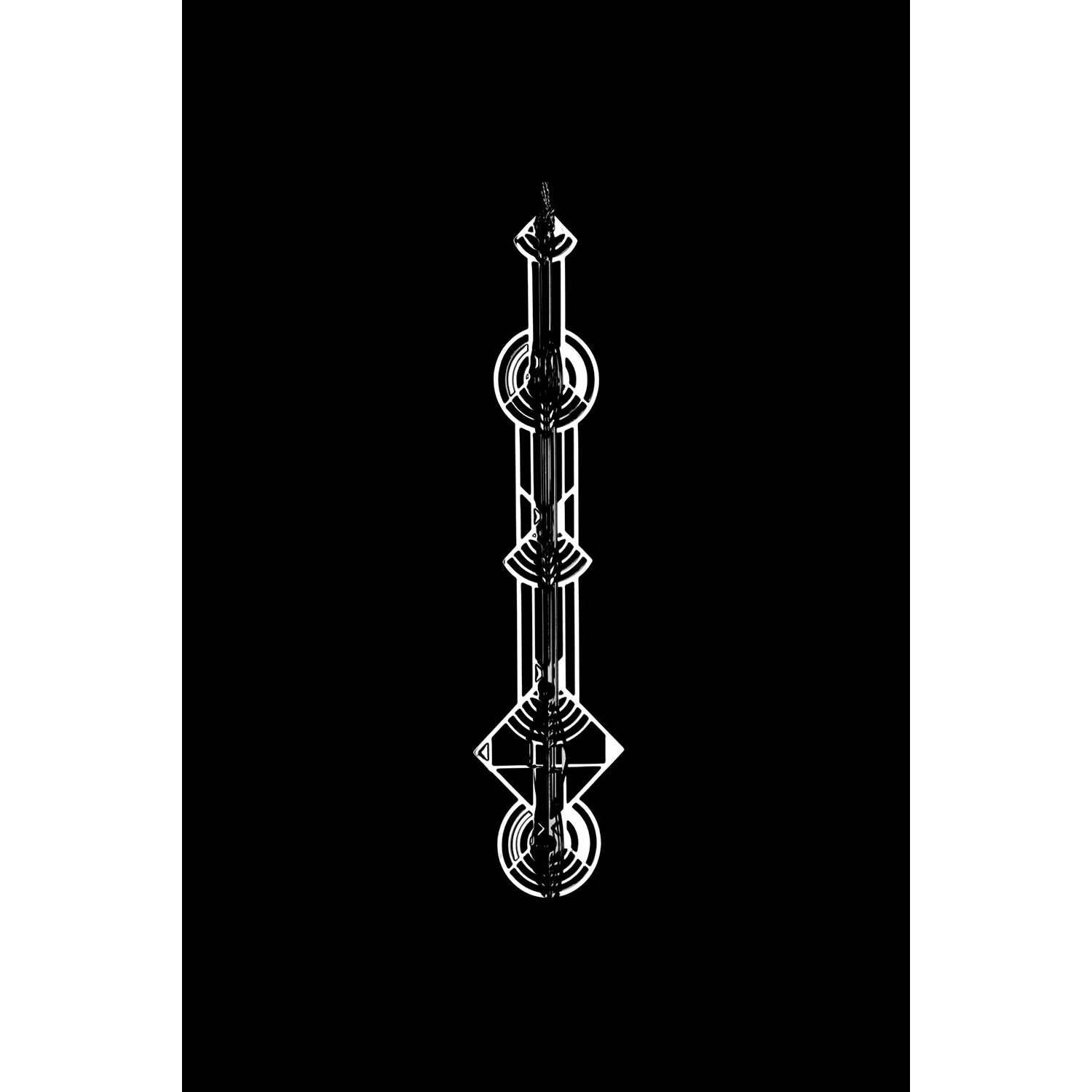

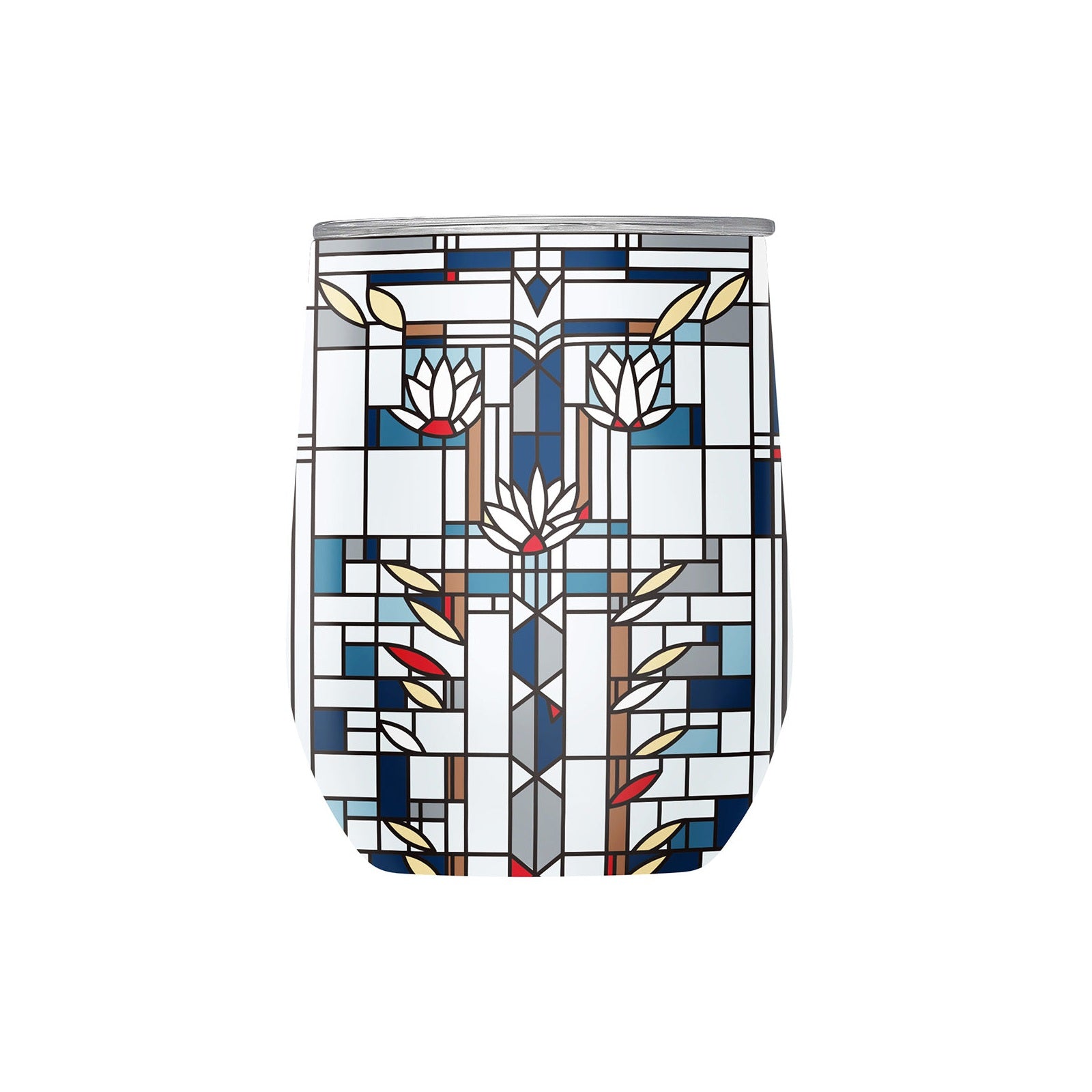

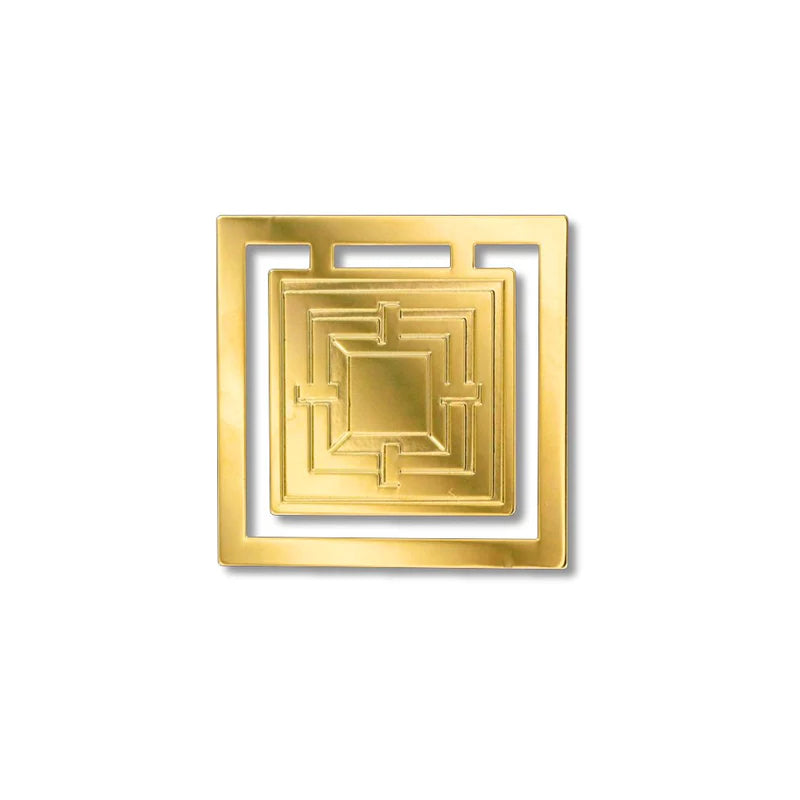

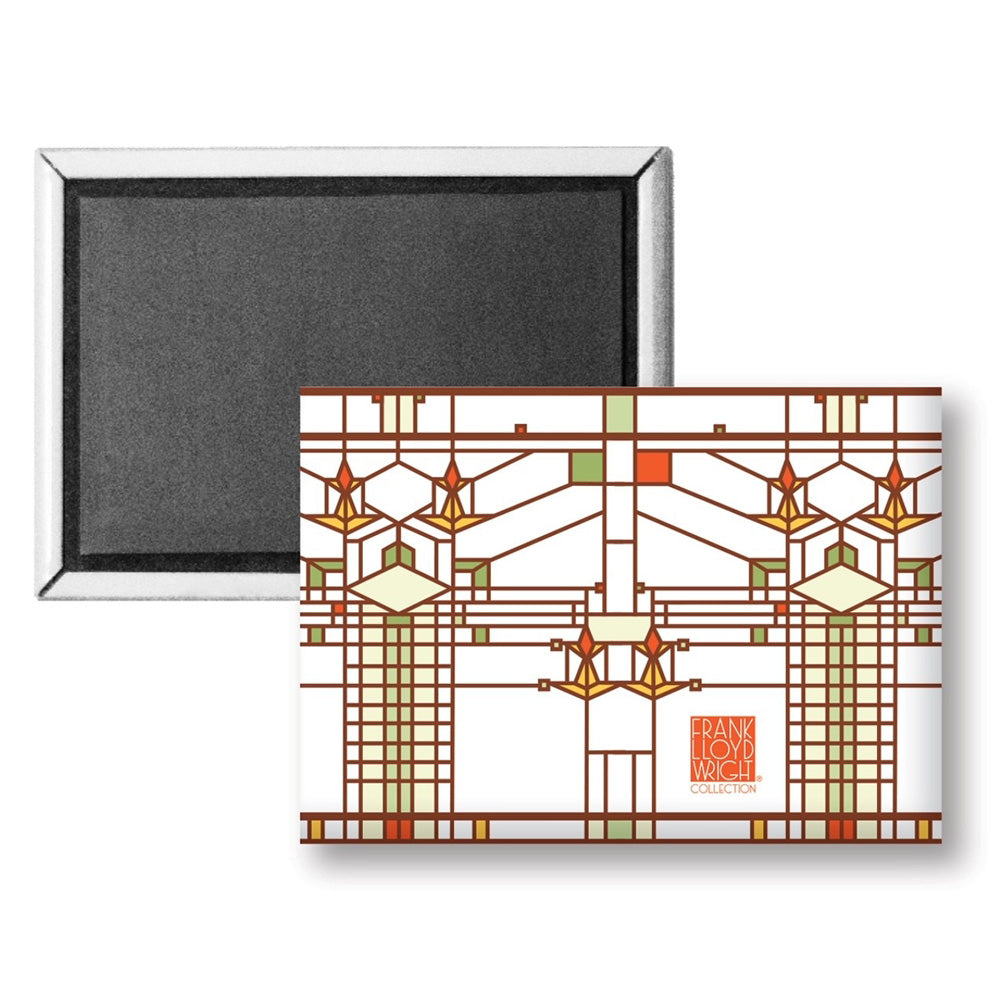

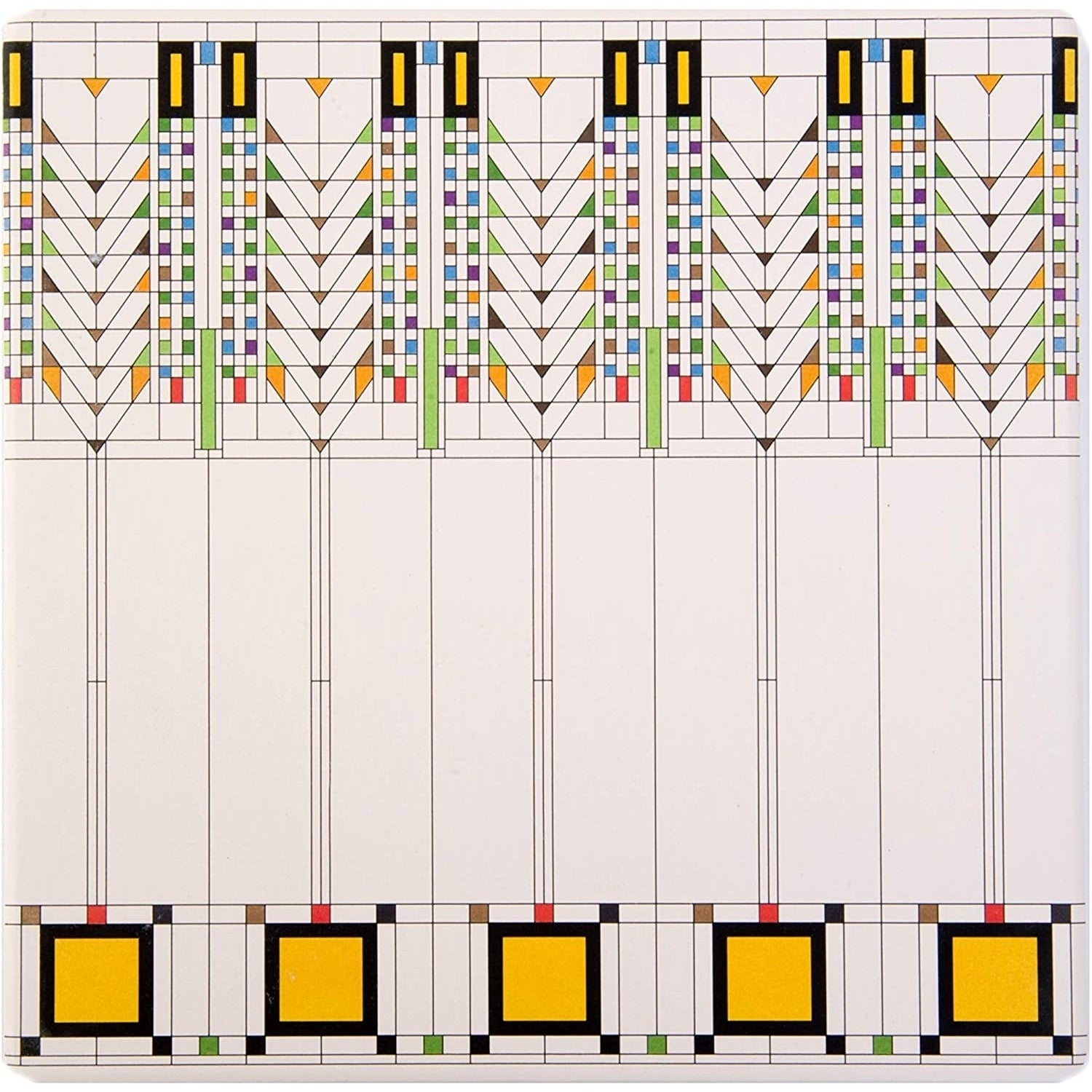

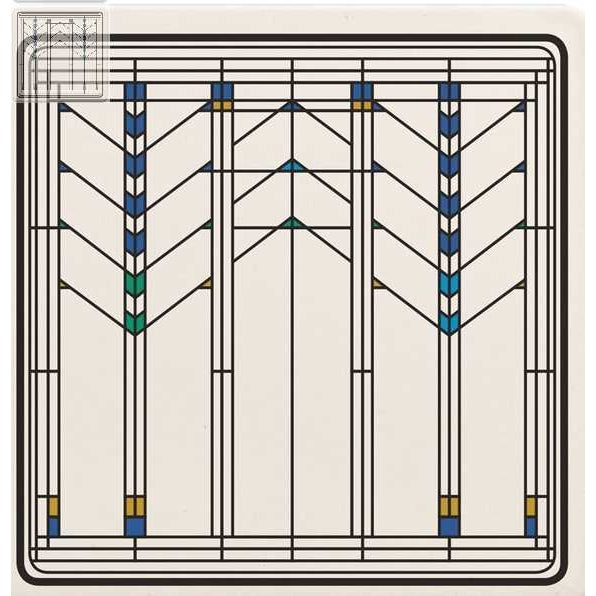

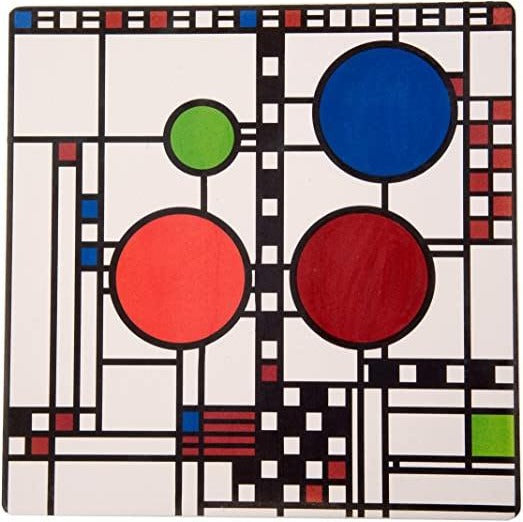

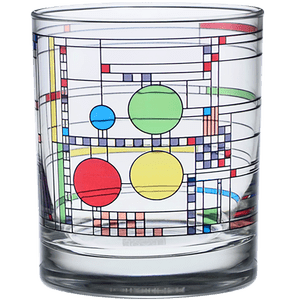

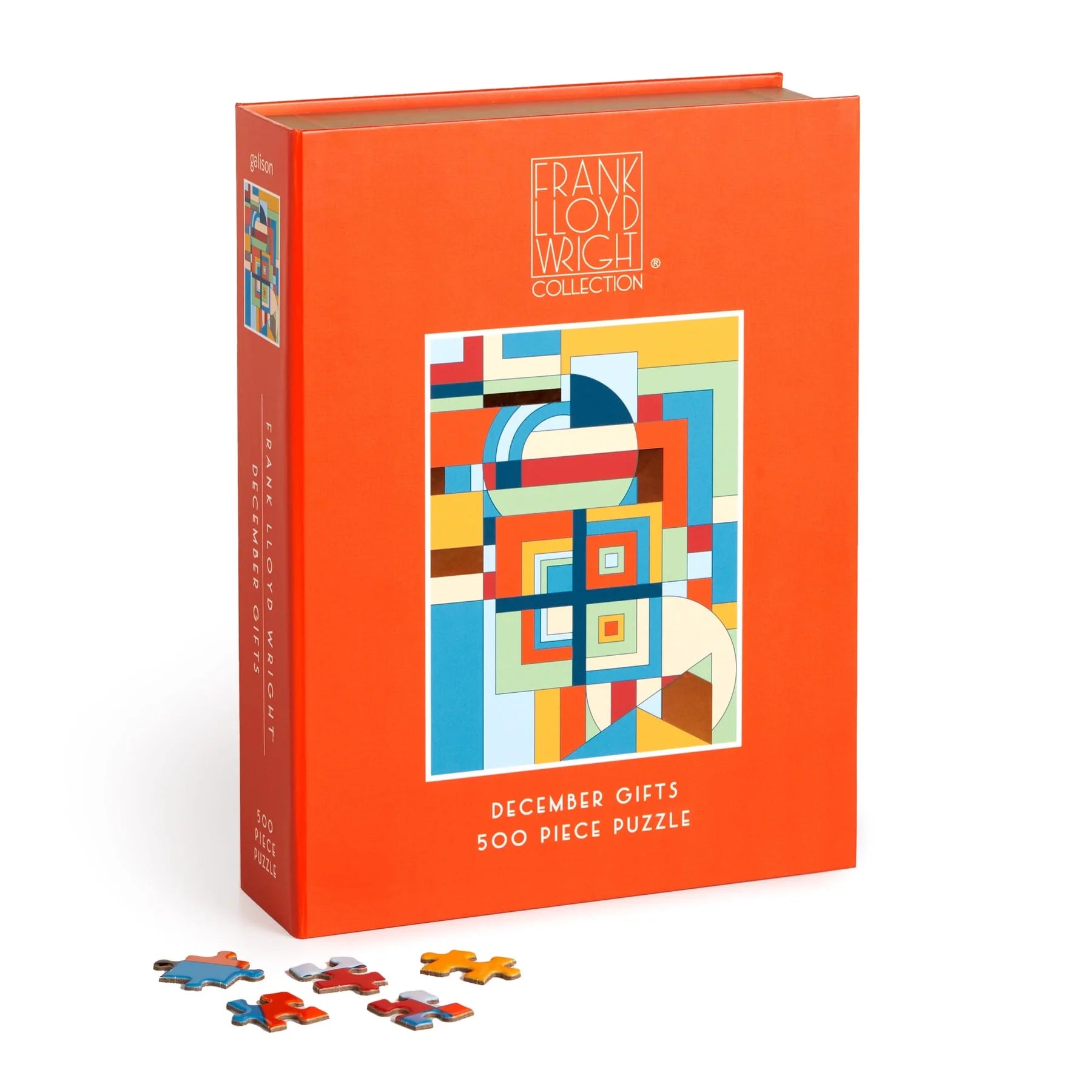

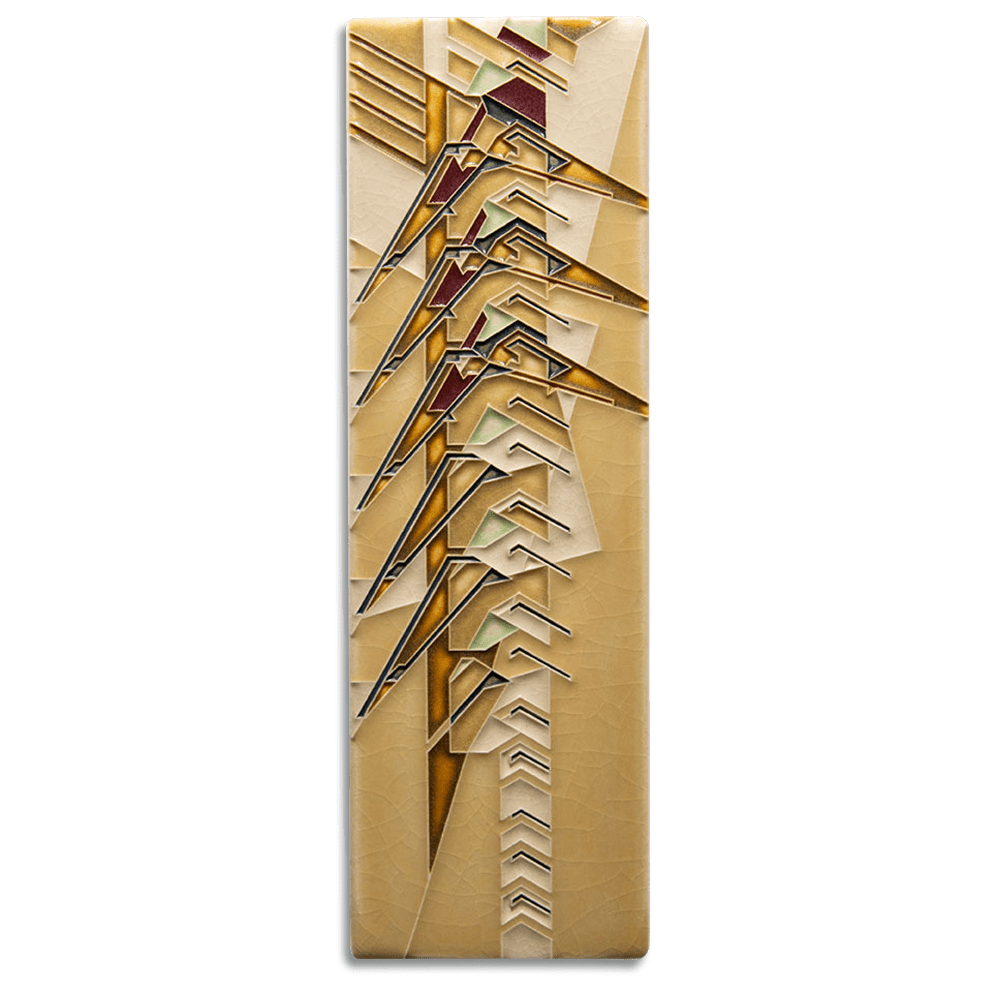

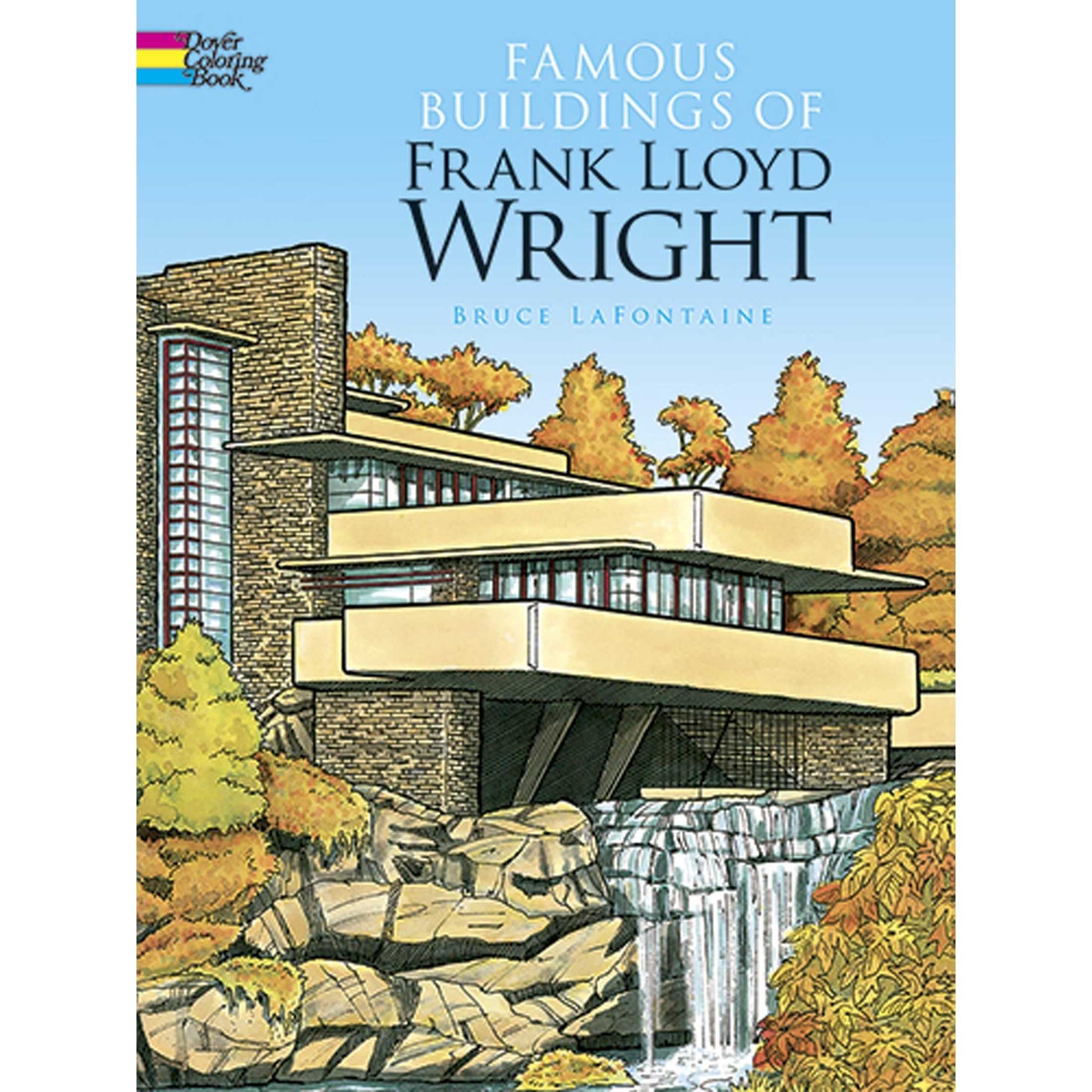

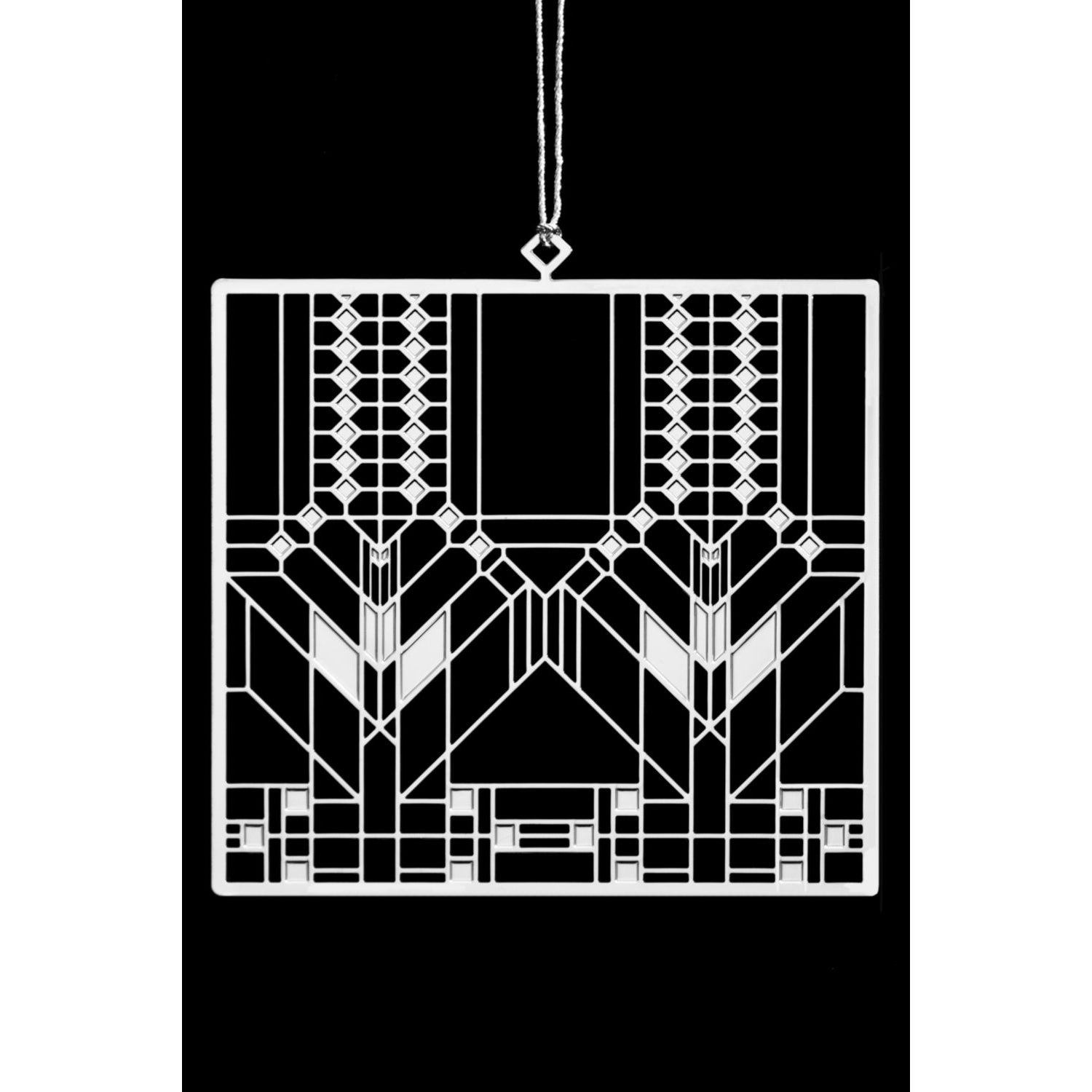

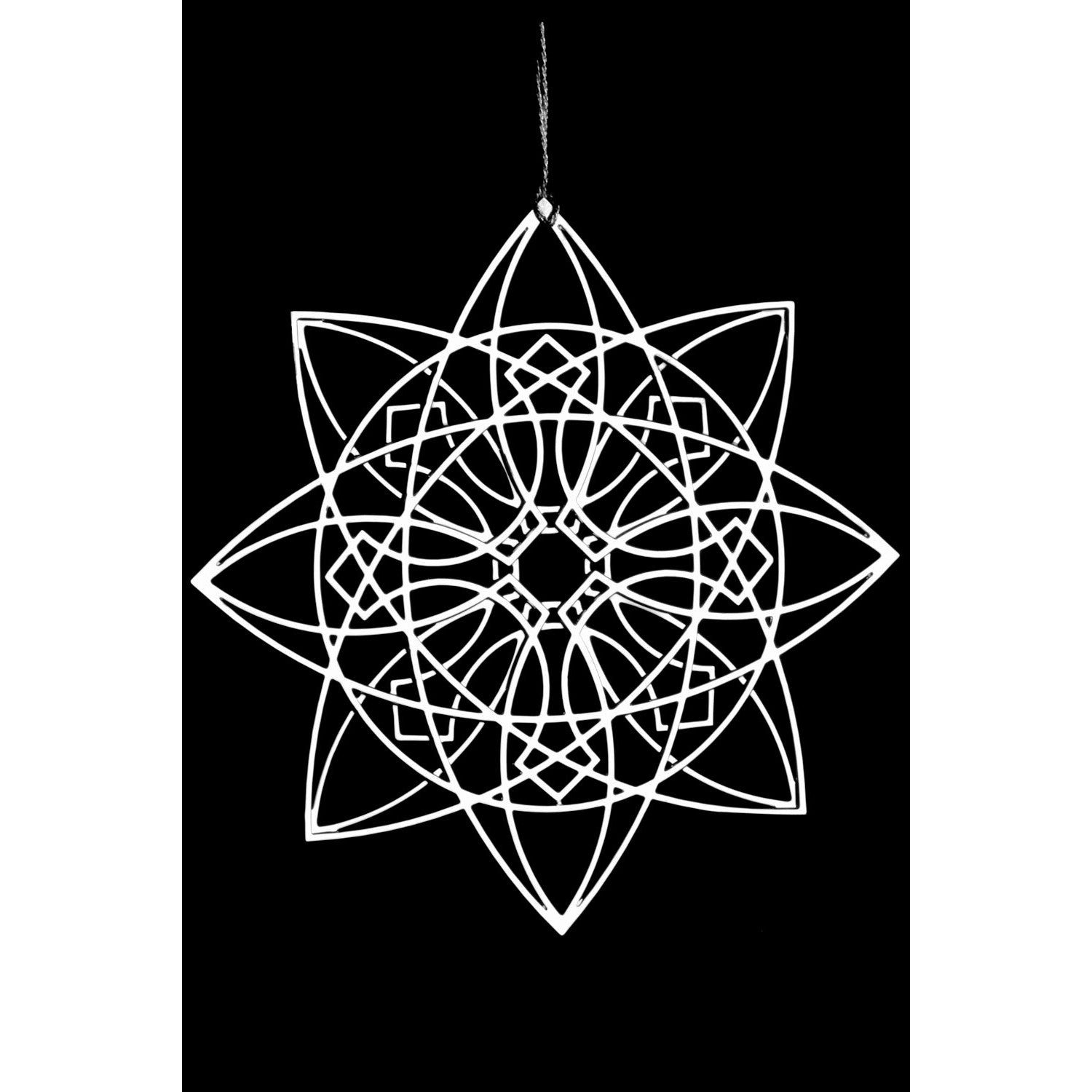

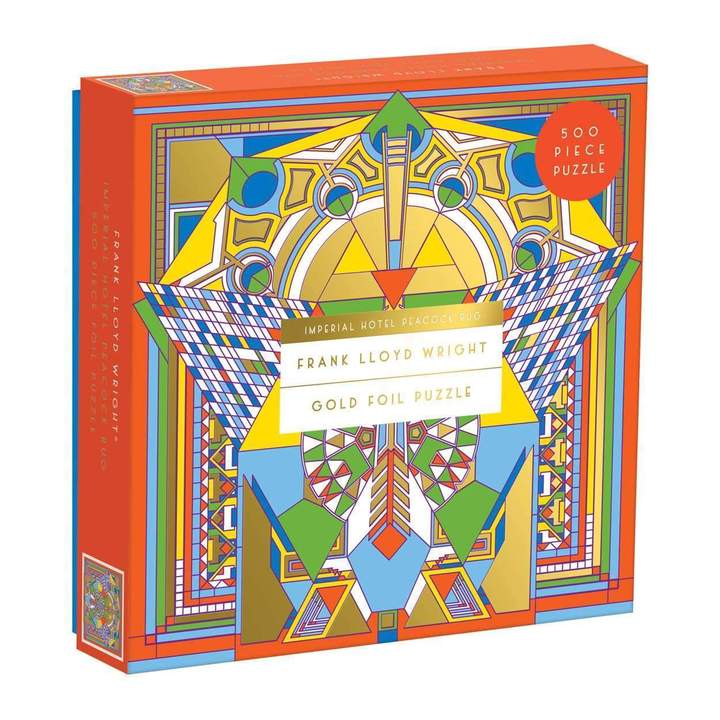

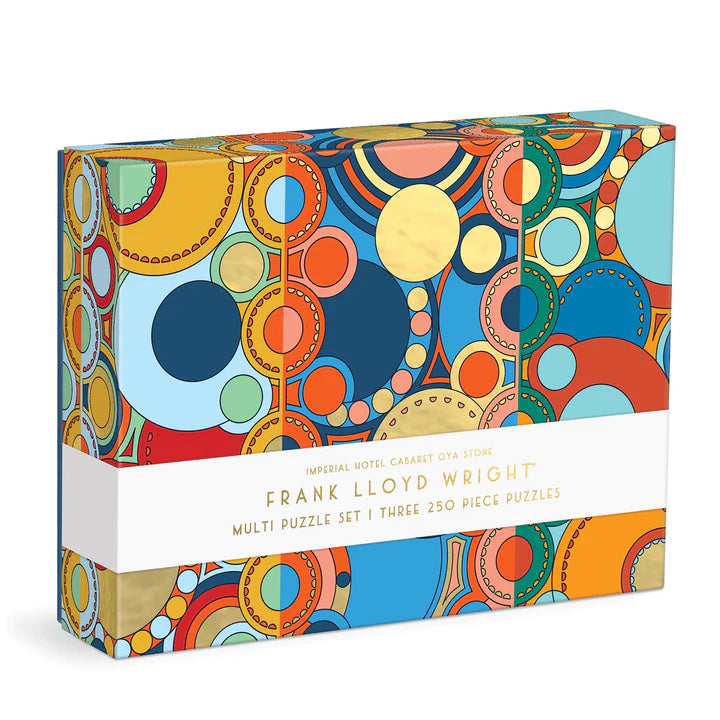

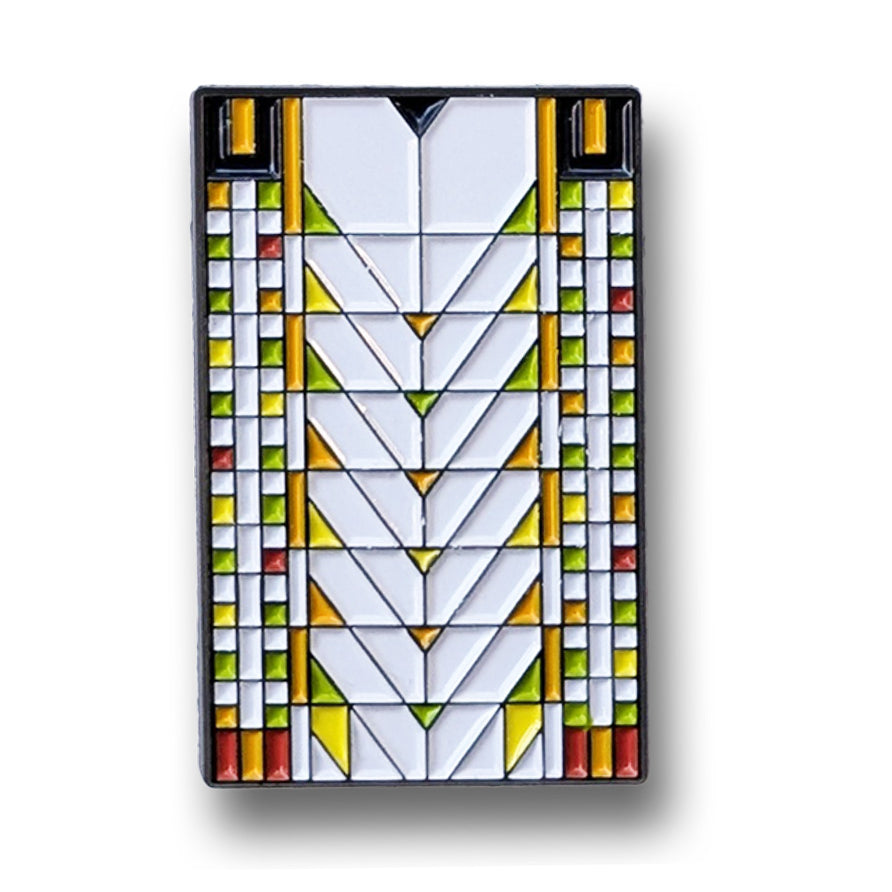

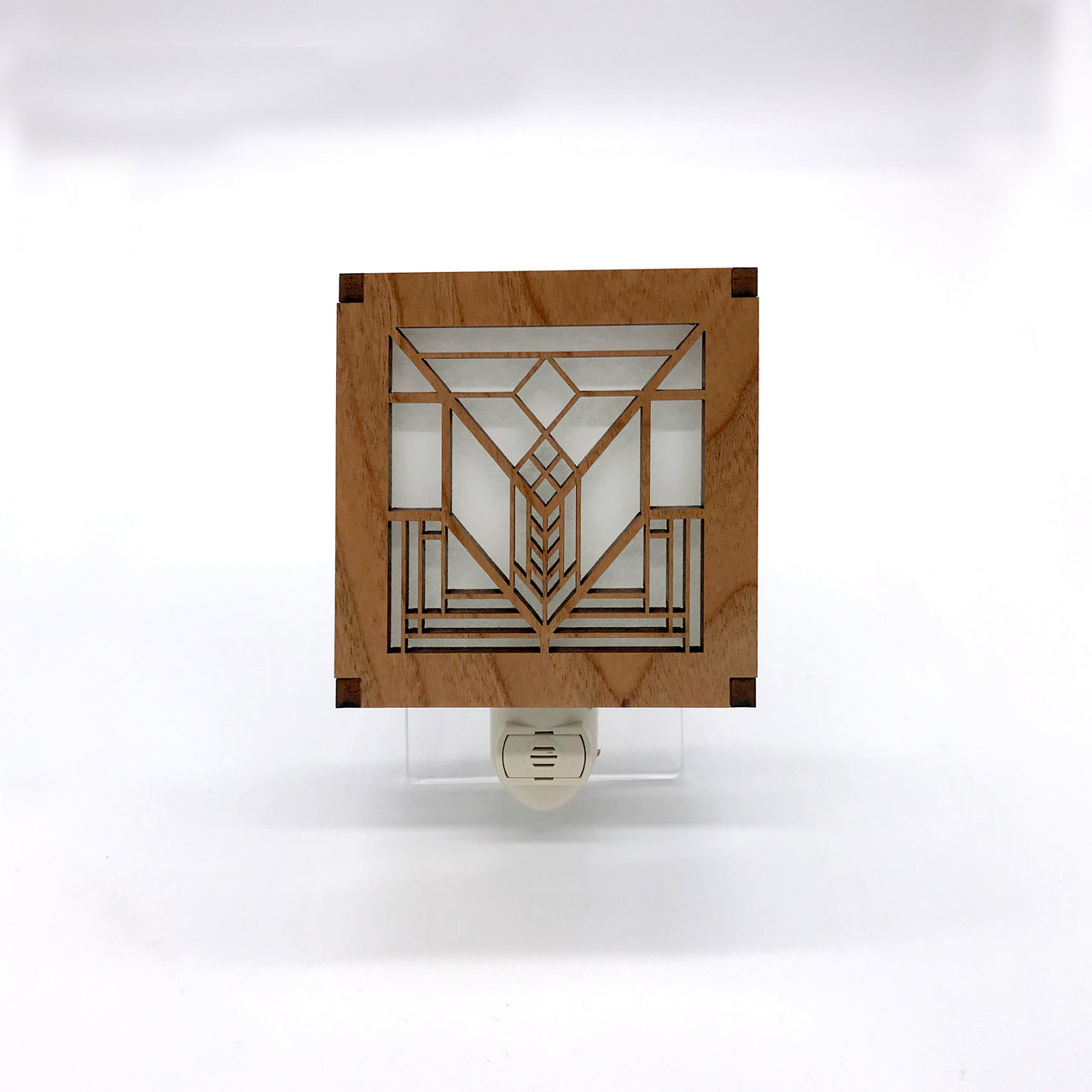

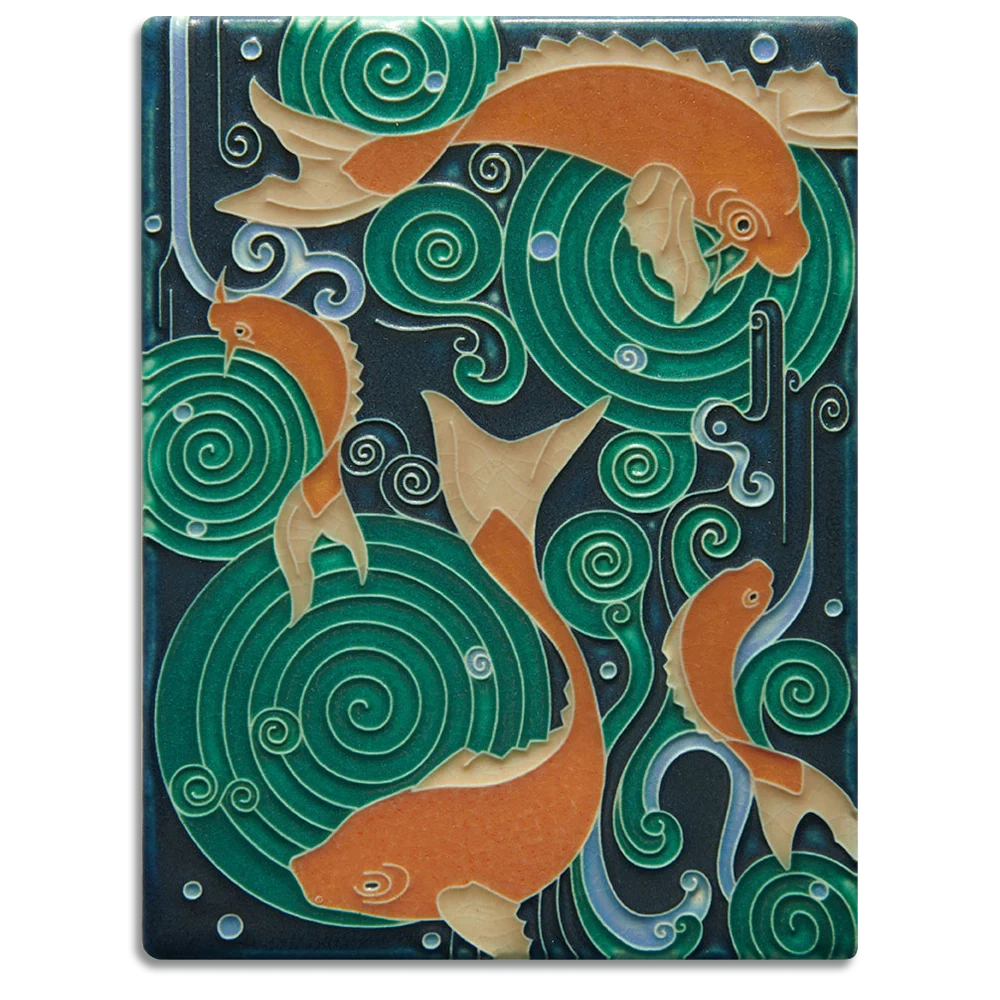

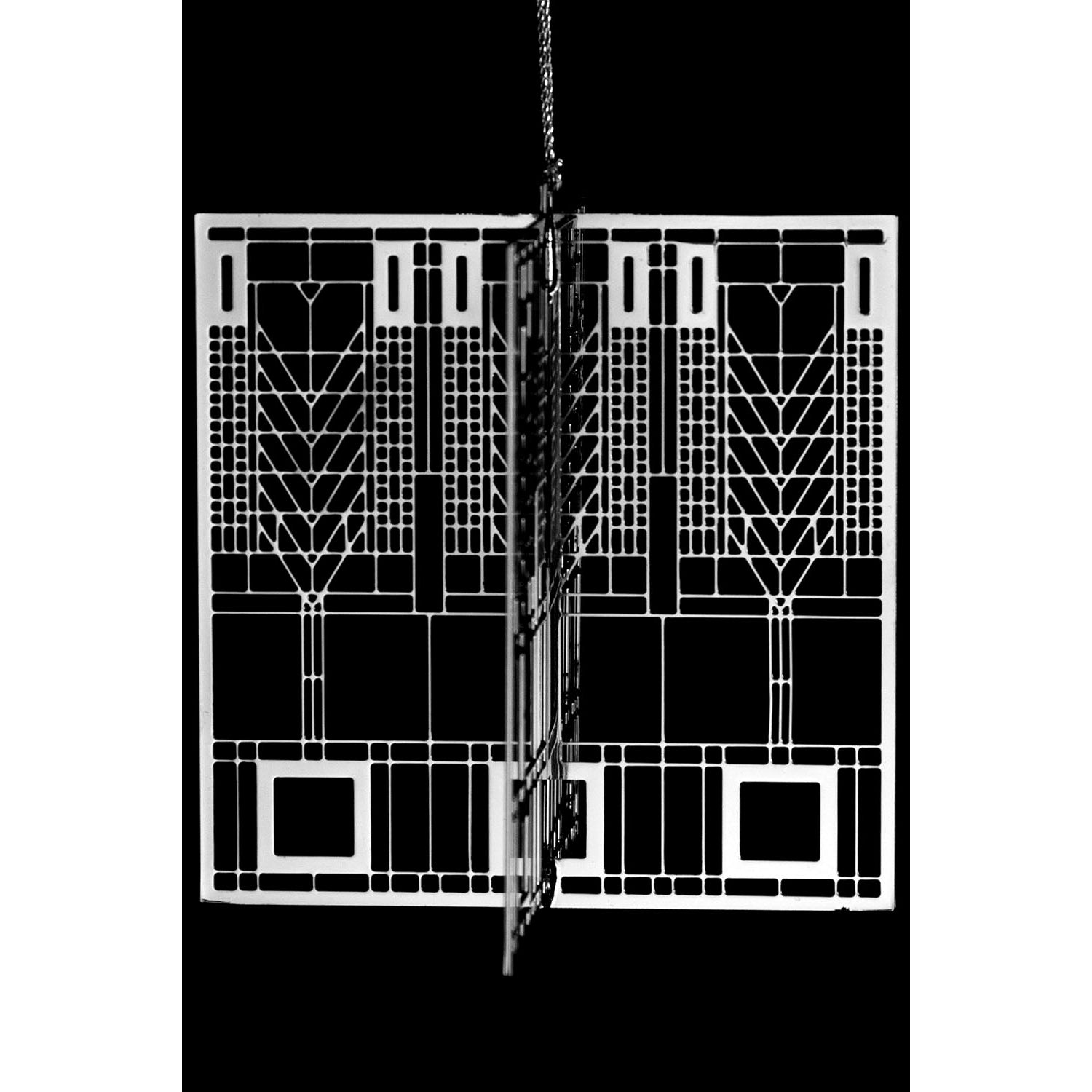

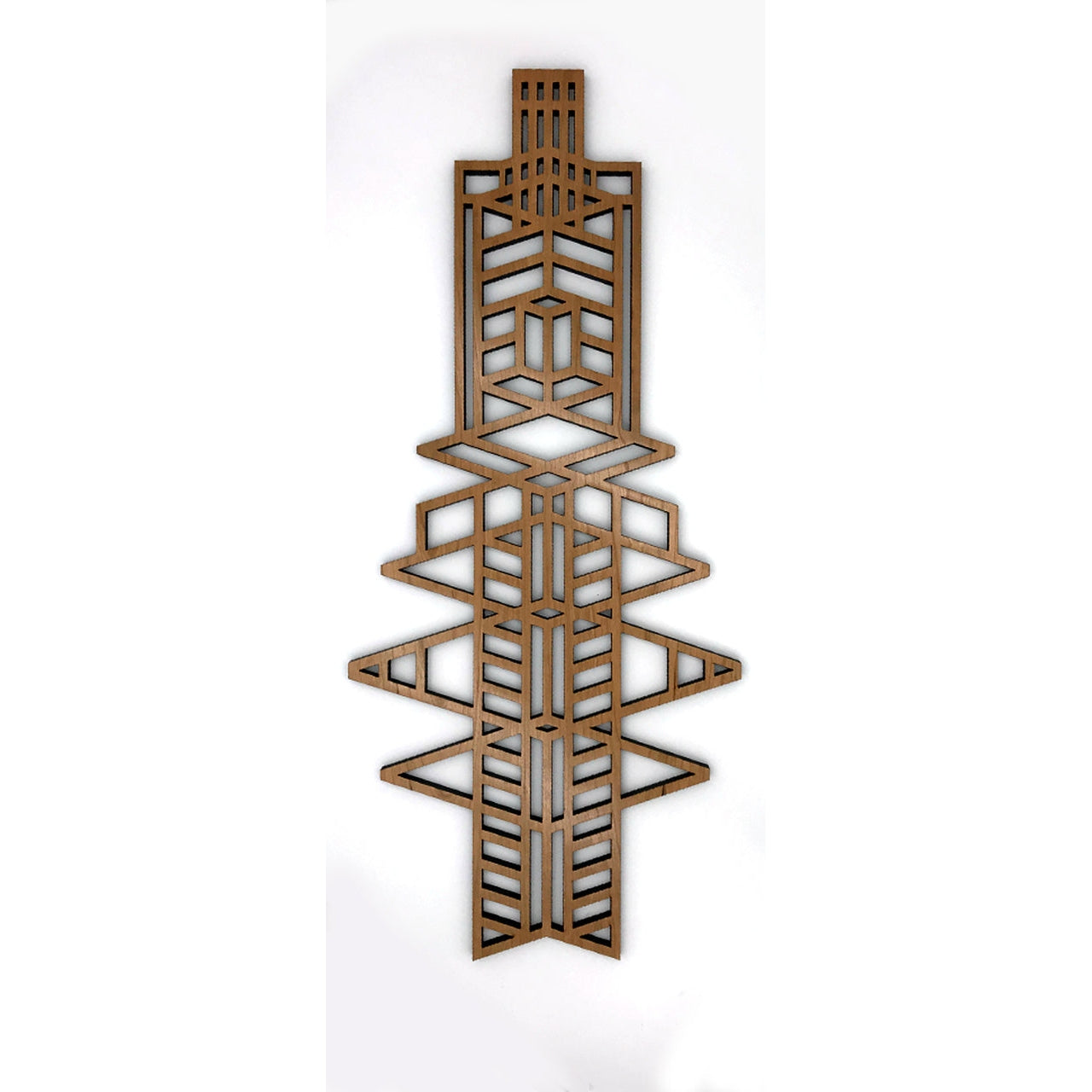

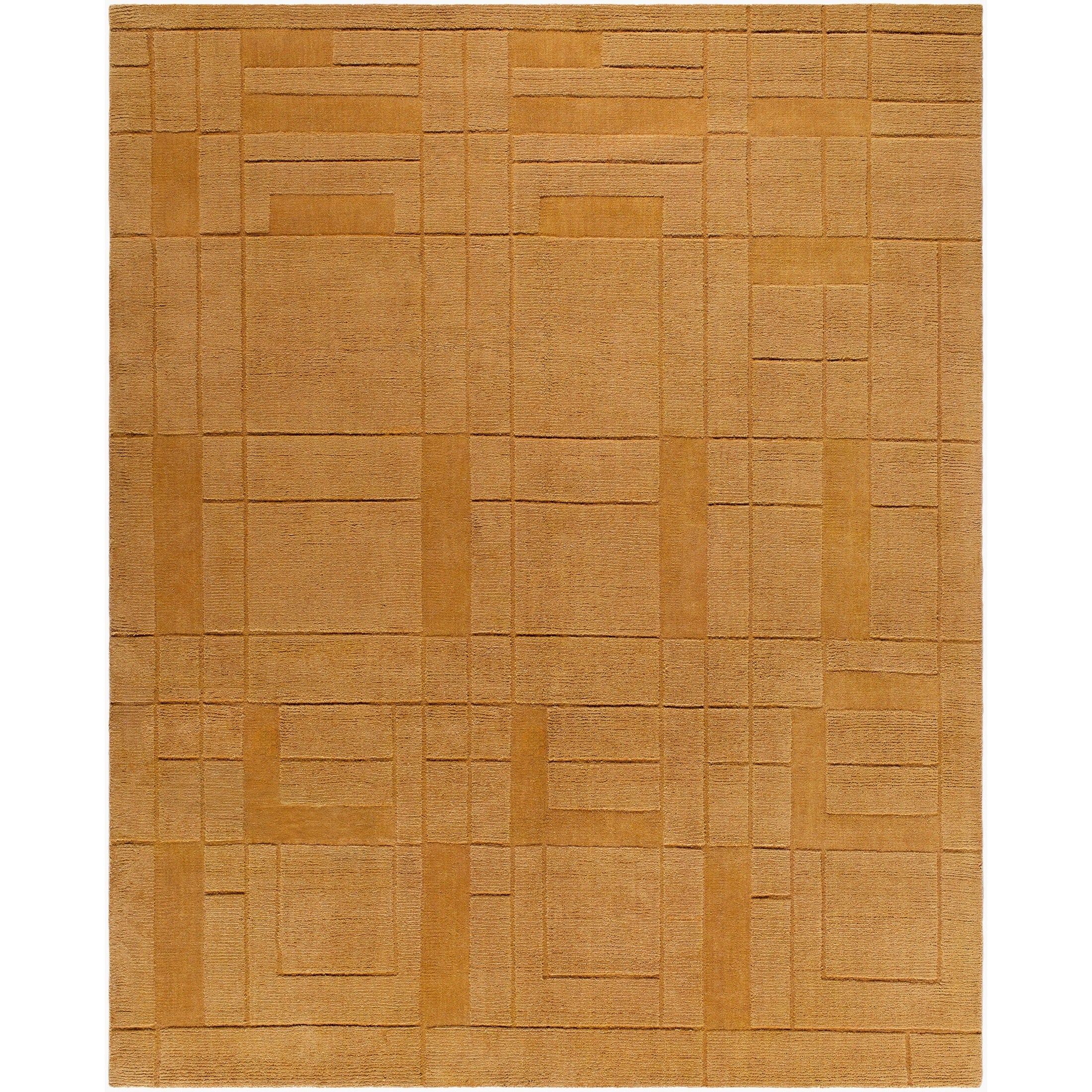

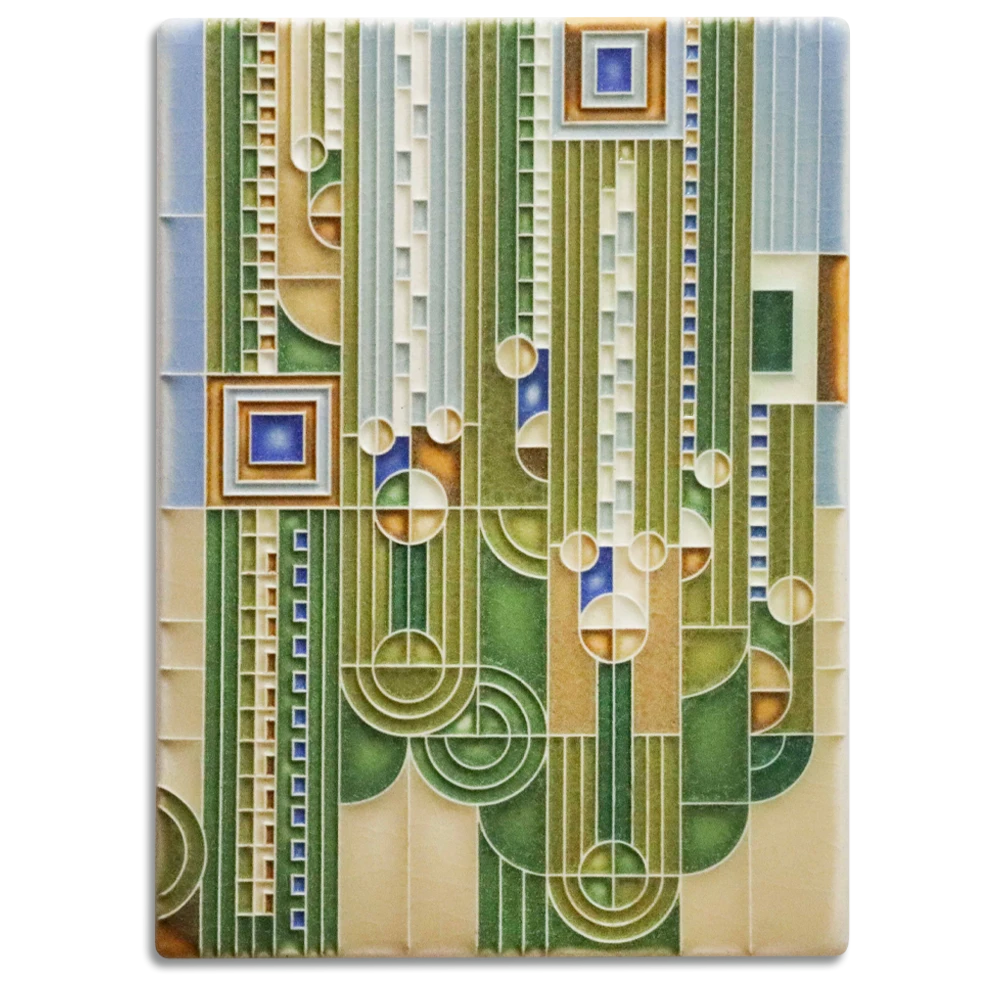

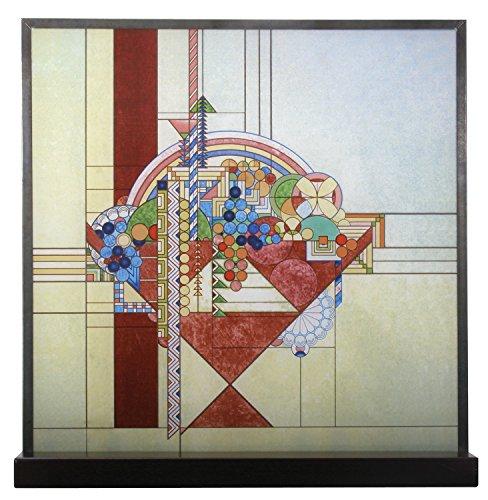

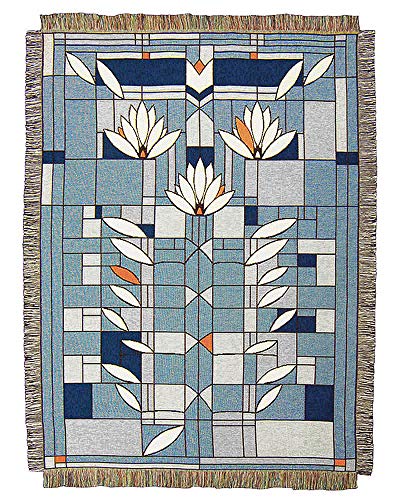

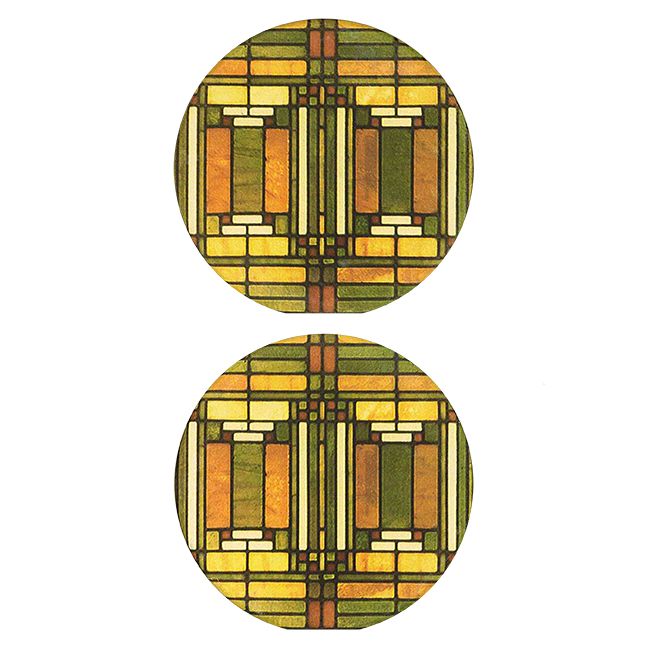

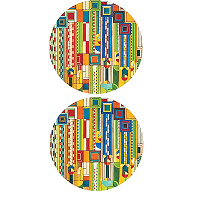

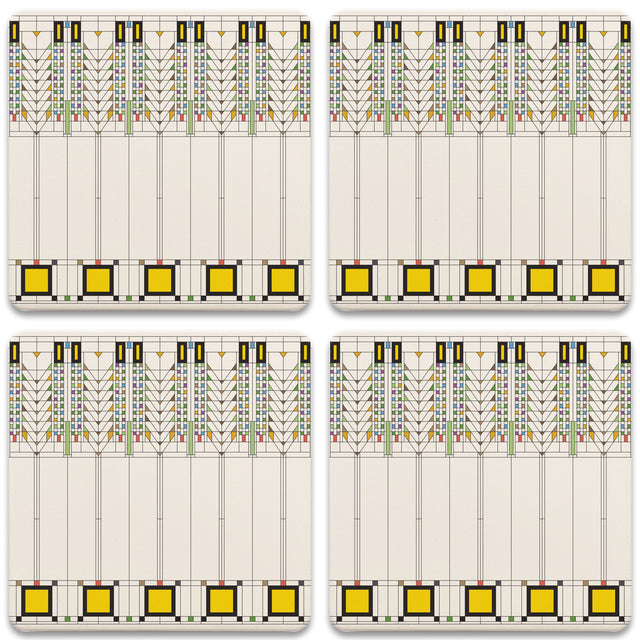

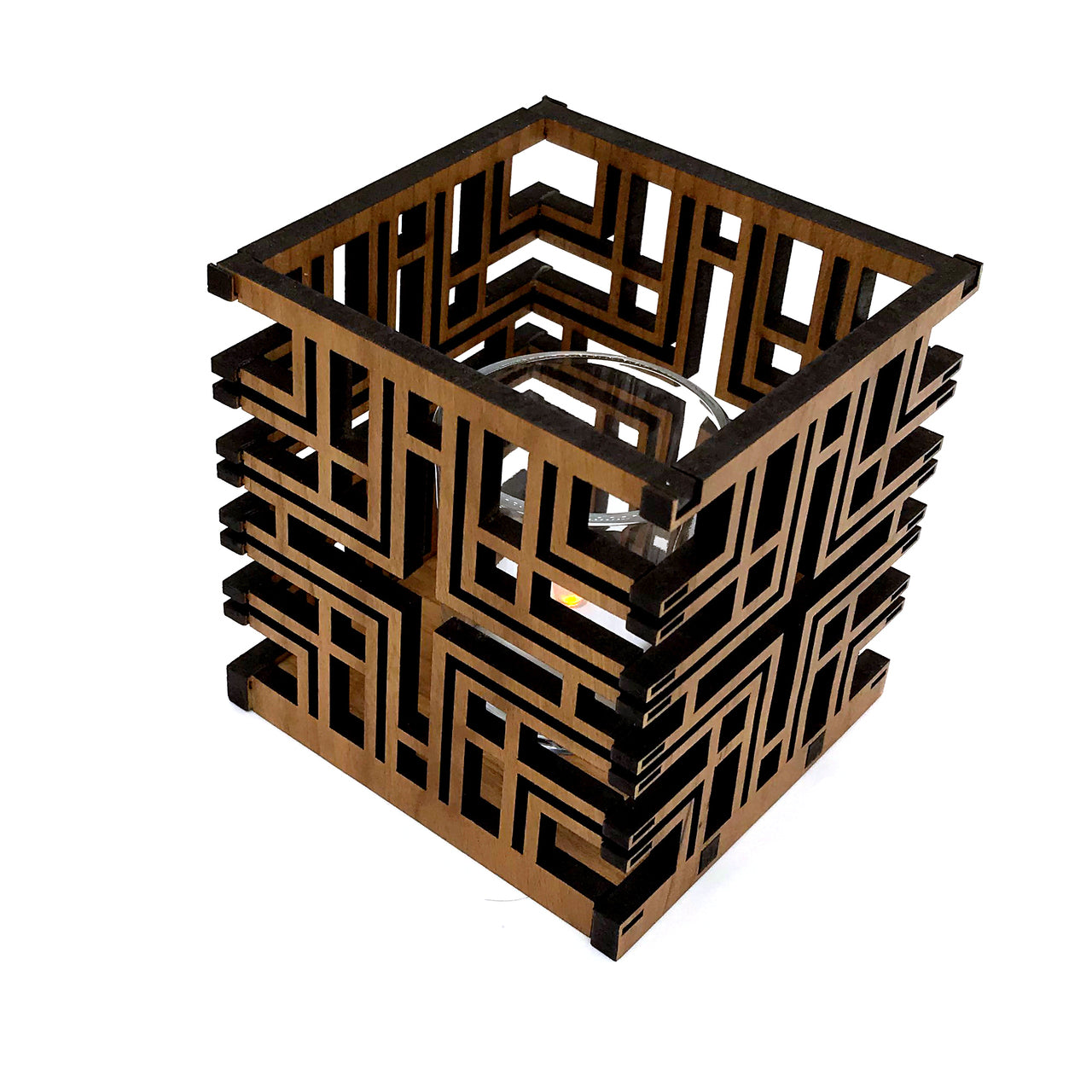

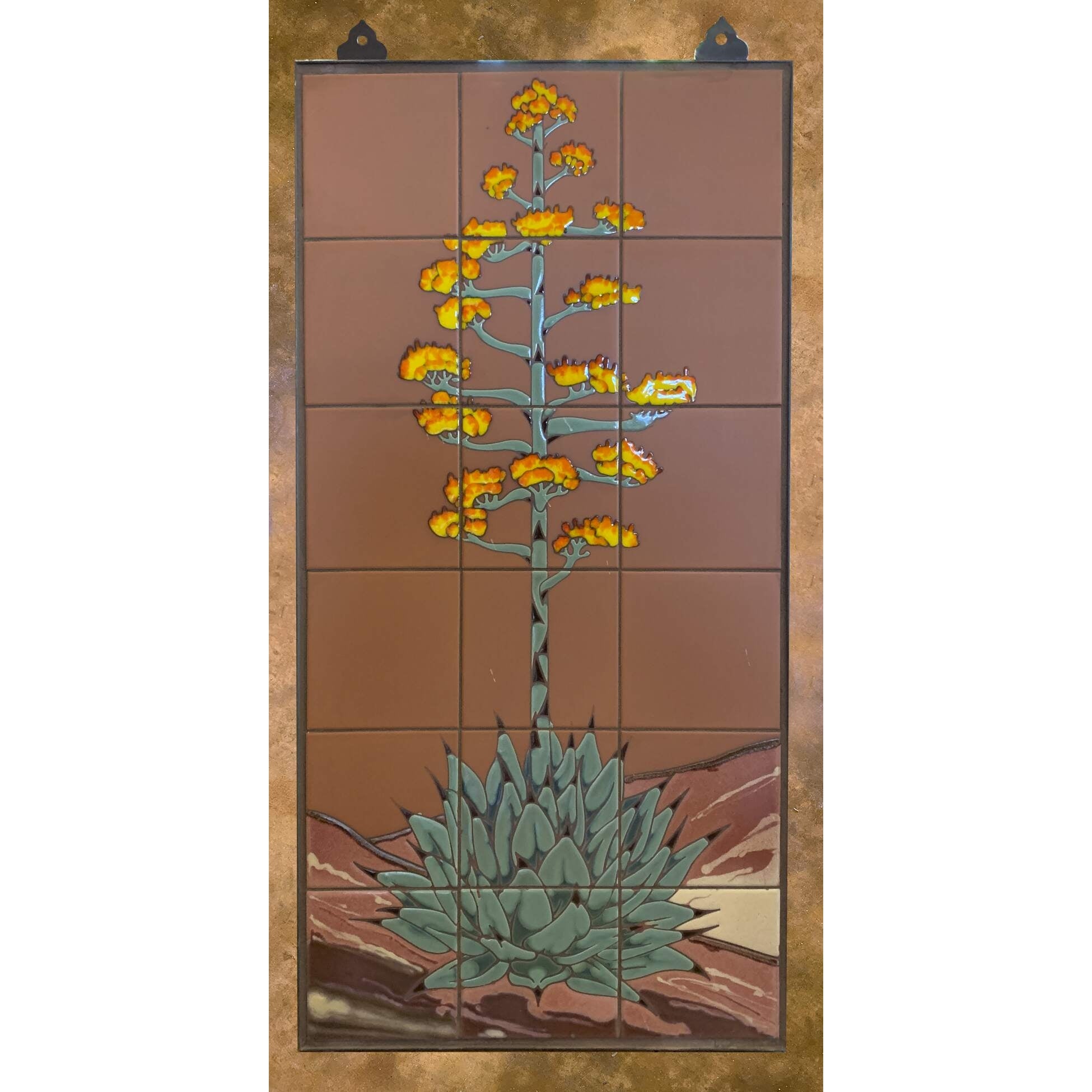

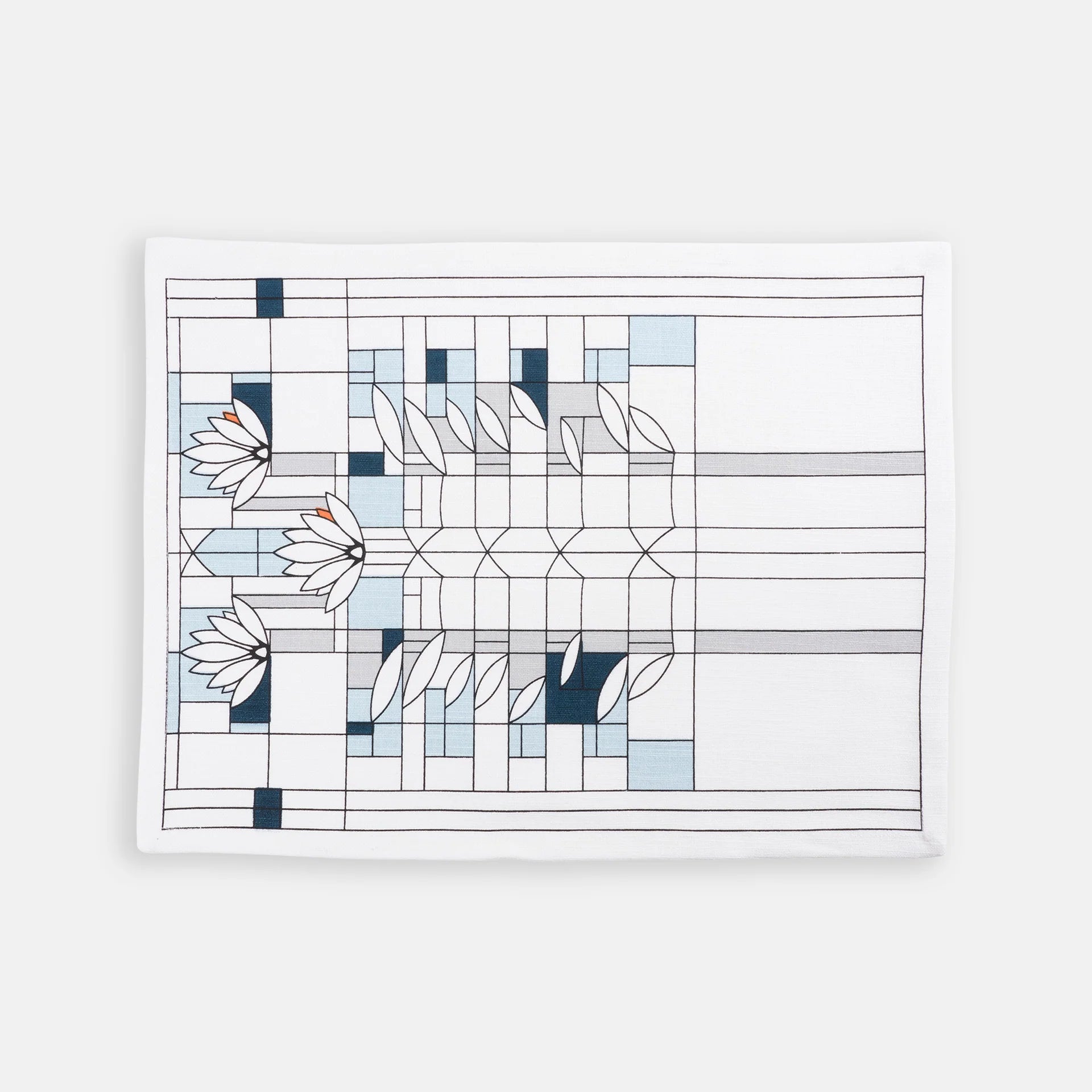

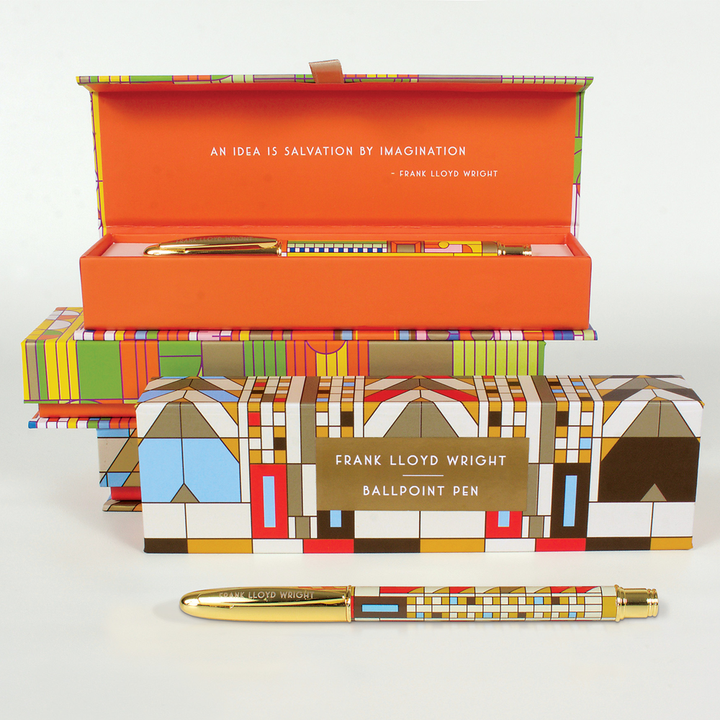

The hotel’s exterior was clad in golden brick and pale Oya stone, with intricate ornamentation including cast concrete patterns, terracotta panels, murals, and custom furniture designed by Wright to harmonize with the building. Despite delays, the hotel opened on September 1, 1923—the day the Great Kanto Earthquake struck Tokyo. Though much of the city was destroyed, the hotel remarkably survived, as confirmed by a telegram from Baron Okura praising Wright’s genius.

Wright never returned to Japan after completing the project, although he continued collecting Japanese prints. The Imperial Hotel was demolished in 1968, but parts of it were preserved and reconstructed at the Meiji-mura open-air architecture museum in Japan.